EDITORIAL: After Decades Of Violence, Plateau Killings Remain Grossly Under-reported

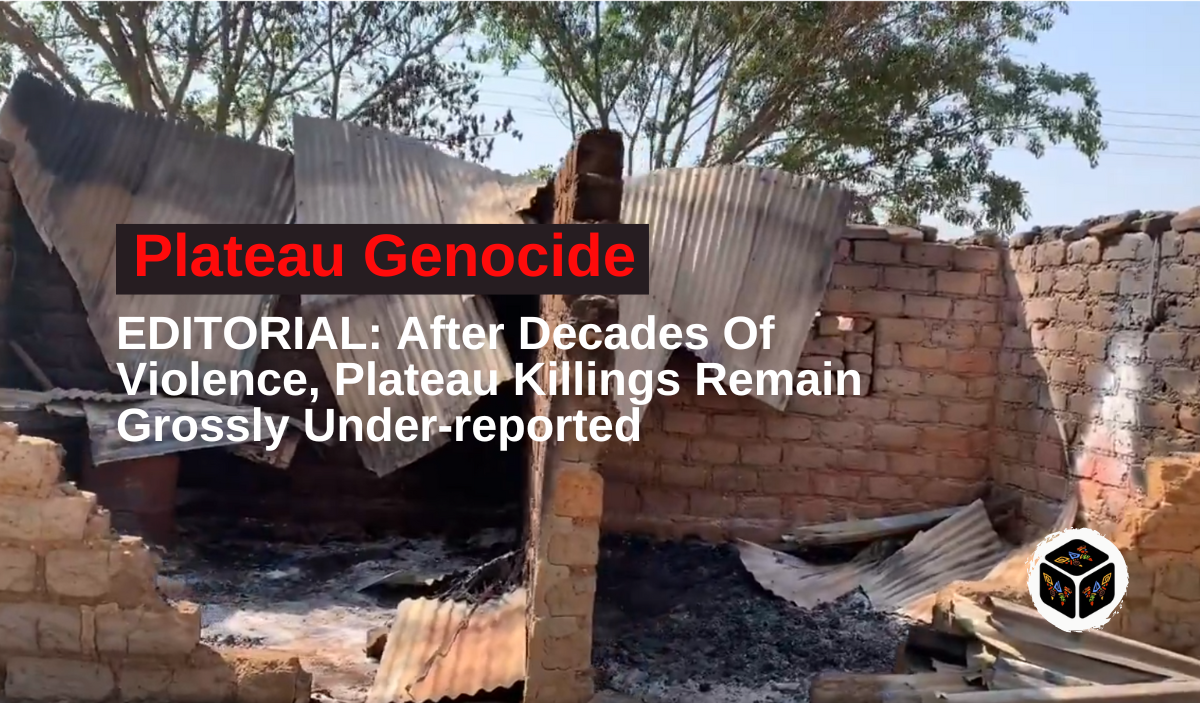

Mainstream Nigerian media has grossly under-reported the genocide and land grabbing taking place in the Middle Belt region of Nigeria. The recent attacks in Bokkos and Mangu Local Government Areas of Plateau State, amongst others, provide clear evidence of the multifaceted and highly sophisticated war being waged on the people of the region aimed to weaken them both physically and psychologically.

These terror attacks are a recurring tragedy with a long, dark history largely helped by the misrepresentation of facts by the media. At the same time, the military disarms indigenes, preventing attempts at self-defence.

The stories of victims and survivors often differ significantly from the government’s official position. Upon closer examination, it is almost always the case that the government’s version of events has obvious gaps, while that of the victims is a lot more complete, coherent and chilling.

While acknowledging that this is a common problem across the Middle Belt which is beginning to spread south, this article focuses on Plateau State. The goal is to tell the story of these genocidal attacks beyond the sponsored propaganda that serves to protect the aggressors and keep their unfortunate victims perpetually vulnerable.

Eyewitness Account of the Christmas Eve Attack

On Christmas Eve, 2023, locals in Bokkos, Barki-Ladi, and Mangu LGA went about their activities in preparation for the Christmas festivities with a warning about impending attacks hanging over their heads. Despite the warning, they did not know that they would shortly not be celebrating with their loved ones, but instead mourning their losses, as a well-coordinated attack by armed terrorists was suddenly unleashed across these communities.

Earlier, West Africa Weekly reported that for two days beginning on the 24th of December, armed terrorists with sophisticated weapons invaded several communities within these local government areas of Plateau State, shooting, killing, maiming, burning and destroying everything in sight, leaving over 150 people dead including women and children, and hundreds of millions of naira worth of economic devastation.

According to reports, the locals had received warnings of impending attacks delivered to their communities by anonymous persons. Over 35 distress calls were made to the state’s security forces, but no action was taken to prevent or stop the onslaught when the attackers kept true to their threats.

Following the incident, the state Governor, Caleb Mutfwang, termed the killings ‘unprovoked’ and ‘unacceptable’, promising that the case would be looked into.

Survivors and eyewitnesses of the recent attack, when interviewed by West Africa Weekly, told tales of horror in the killings that have drawn general condemnation from within and outside the country.

They also called on government and NGOs to remember that they have fled their homes and need humanitarian aid to survive.

An anonymous survivor said:

“The criminals have a religion. It is not an indictment on any religion to state the facts. We have indigenous Muslims in our communities, and we intermarry with them; they are very peace-loving. But sadly, the terrorists sometimes exempt people they know to be Muslims. They separate them from the rest of us before they start the killings.”

“When the Fulanis initially came, we accommodated them, and now they are killing us off and taking over our ancestral lands. They attack at night to catch us unaware and disoriented, and we cannot even defend ourselves.

“Does it mean that the Fulani race is a bad one? No. It only means that bad eggs are around, and the good ones have sheltered them. So if you wouldn’t want your people to be profiled, give the terrorists up to the authorities.”

Out of the 18 people killed in Maiyanga village, 10 were relatives of Mandong Jalang. Speaking in an interview, he said:

“My father, David Jalang, was killed, and four of my cousins, Emmanuel Jalang, Fidelis Jalang, Gaius Adamu and Matawal Gaius, were all killed. Then, on my mother’s side, three of her brothers, Solomon Langwen, Mafulul Langwen, Nafor Makut and Maren Masok, were killed, and her uncle’s wife, Mildred Makut, was also killed. So, out of the 18 people who were killed during the attack in my village, 10 were related to me. Thankfully, my mother fled the village in the evening when the attackers were in the neighbouring village; she left the village only with what she was wearing, that was how she survived, and she has not been finding it easy, but we thank God. Apart from the loss of lives, all our properties, every single thing was burnt to the ground. We were not left a pin.”

History of The Plateau Killings

Over two decades, tensions between ethnic groups have been rooted in electoral competition, fears of religious domination, and tussles over land rights. Over time, these have merged into an explosive mix, to which several thousand lives have been lost since 2001 when the first major riot broke out.

According to a document by the Plateau Peace Building Agency, the crisis followed the April 12th, 1994 riot instigated by the appointment of Alhaji Mato (a Muslim) as sole Administrator of Jos North LGA (a predominantly Christian area). The appointment was promptly rejected by indigenous groups, resulting in a riot that claimed the lives of five persons and the destruction of properties in Gada Biyu. This would be the first of many conflicts the state would record in the coming years.

After this initial boiling-over, it became clear that the narrative had decisively turned into that of an undeclared ethno-religious war. It was clearly established that there was an ongoing contest between Hausa-Fulani (Muslim) and indigenous (majorly Christian) groups over ownership of Jos North.

There was also political competition in the form of indigene (majorly Berom) vs settler (Hausa/Fulani) issues. The atmosphere in Plateau, already tight with these ethno-religious tensions, was further aggravated by the controversial appointment of Alhaji Muktar as NAPEP Coordinator for Jos North LGA – an appointment that was rejected by indigenous groups (Afizere, Berom, and Anaguta).

Then came the September 7, 2001 crisis, which lasted for six days and cost at least 1000 lives, along with several homes, businesses and places of worship. Subsequently, long-standing tensions within smaller towns and villages in the state escalated into violence.

The killings came to a halt only when the federal government declared a state of emergency in 2004 after about 700 people had been killed in an attack on the town of Yelwa in Shendam LGA. The cause of this crisis was the retaliation of Christians against Muslims for the murder of 46 Christians, a subsequent reprisal attack, and the expulsion of the remaining Christian population in Yelwa in February.

Owing to the unresolved issue of indigency and ownership of Jos, combined with religious hostility, yet another crisis ensued in the state between Christians and Muslims again in 2008, claiming at least 1000 lives, with several thousand displaced from their homes and properties.

In January 2010, a dispute between Christians and Muslims would once again claim the lives of nearly 400 people and spiral into a nighttime attack by Fulani militias on Dogo Na-Hawa and Rasat villages in Jos South LGA in March 2010.

The 2010 Jos Crisis was a new wave of violence as it saw the introduction of bombs as weapons used by a new breed of violent Islamic fundamentalists (Boko Haram). The first such attack was in the Angwan Rukuba area on Christmas Eve 2010 where 80 people died, summing up to a total death toll in 2010 of about 780.

With the introduction of bombs into the arsenal of the terrorist group, Plateau began experiencing a continuously high level of violence, characterised by a uniquely fierce type of brutality in the subsequent years, as the migrated Fulani who settled in Jos repeatedly attacked the indigenous (mostly Berom) people of the state and other perceived Christian groups.

This new level of violence consumed thousands of lives, and several more were displaced from their homes and ancestral lands into poorly-run IDP camps. There was also extensive damage to properties belonging to indigenes of the land, as houses, vehicles, and worship places were burned down.

In 2016, the narrative took a new dimension. While underlying ethnoreligious hostilities remained unresolved, it also became an issue of conflict between pastoralists and crop farmers as cattle owned by Fulani pastoralists repeatedly devastated numerous farmlands belonging to indigenes.

As these indigene vs. settler battles have taken the form of religious crises and land rights battles, Plateau has experienced a uniquely high level of ethnoreligious cleansing and land-grabbing over the space of two decades.

While the government usually makes attempts to control the situation after the attacks have been carried out, no effort has been made to punish any offenders.

Government Intervention After the Attack

Despite promises made by the government and security forces, there was little or no visible military intervention to prevent the attack promised by the terrorists on the 30th of December, leading to preventable loss of lives in the same Local Government Areas.

For the first time since the 1980s, all the Service Chiefs were in Jos at once. Many believed it was due to the attention that particular attack garnered nationally and internationally. The Chief of Naval Staff, Chief of Defense Staff, Chief of Air Staff, Chief of Army Staff, Minister of Defense, and Minister for Humanitarian Affairs arrived in Plateau State to assess the situation after the December 2023 attacks.

The vice president had earlier visited the state and promised that the presidency would look into the situation and offer lasting solutions. The National Assembly had also summoned the Service Chiefs to report on the crisis situation.

Before then, a motion on the urgent need to investigate the killings on the plateau was moved by Rep. Yusuf Gagdi on April 13, 2022. No further information about the motion has been released to the public since then.

The current first lady also sent money to the victims of a Christmas Eve attack, but the people say they are tired of monetary compensation with no plans to secure their lives and lands.

About The Author

Mayowa Durosinmi

author

M. Durosinmi is a West Africa Weekly investigative reporter covering Politics, Human Rights, Health, and Security in West Africa and the Sahel Region

Related Articles

Tinubu Deducts N100bn Monthly From Federation Account Without Approval El-Rufai Alleges Says Action Deserves Impeachment

Former Kaduna State Governor Nasir El-Rufai has launched a blistering attack on...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 26, 2026After Taiwo Oyedele’s Denials, Lagos State Activates ‘Power of Substitution’ Under Tinubu-Altered Tax Law, Allowing Authorities to Redirect Payments Without Court Orders

Lagos State has moved to activate a controversial enforcement provision in the...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 26, 2026Ivory Coast to Buy Unsold Cocoa to Support Farmers

Ivory Coast has announced a government plan to purchase unsold cocoa stock...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 23, 2026Ghana Moves to Reclaim Kwame Nkrumah’s Former Residence in Guinea

Ghana has embarked on a diplomatic and cultural initiative to reclaim the...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 23, 2026