Power outages Spark Protests in Nigerian Universities, Deepen Educational Inequalities

Sodiq Adebayo is a penultimate student of Chemistry at the University of Ibadan. He seldom has power on his phone and laptop to read or conduct research. His course curriculum requires spending more hours in laboratories than classrooms, but persistent power outages force his lecturers to cancel lab sessions.

Adebayo, the first to attend a university in his low-income family, can’t help but worry about whether he can compete with peers from private and international institutions when he enters the job market. This is the reality of many students in public-owned universities and polytechnics in Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria.

Despite being the largest oil producer in Africa, Nigeria grapples with an energy crisis that has persisted for decades. The majority of the citizens cannot afford five hours of electricity per day, while some do not have electricity at all. This is despite huge investments by successive governments. From former President Olusegun Obasanjo to incumbent President Bola Tinubu, the Nigerian government has squandered trillions of naira to improve the Nigerian electricity supply.

From 1999 to 2015, at least N2.74 trillion was spent by the federal government in the power sector. A report said Nigeria spent N1.7 trillion on power between 2018 and 2020, while another report revealed that over $7.5 billion was spent on electricity transmission alone under Buhari. Also, between 2017 and 2022, GenCos and DisCos received approximately N1.5 trillion from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) as loans.

But all that the country has to show for these huge investments is chronic darkness and less than 5,000 megawatts for its over 200 million population. Electricity shortages continue to weaken businesses and financially frustrate households as people depend on noise-making fuel/diesel-powered generators and expensive solar energy.

After the privatisation of the power sector in 2013, which ushered in private investors in the generation and distribution of electricity, prices were set for the distribution companies by the Nigeria Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC), and the government subsidised the companies to help recover costs that they can’t pass on to customers. However, over 10 years later, both parties (the government and the investors) trade blame for the lack of improvement in the sector.

Earlier this year, President Tinubu pulled the subsidy on electricity, causing an increase in tariffs. Following the removal of the power subsidy, the NERC announced a 240 per cent hike in the tariff for Band A customers.

As a result, businesses pay more for unstable electricity while many have left the country. Meanwhile, the energy crisis has infected federal universities and is taking its toll on students. It deepens educational inequality in a country where about 70 per cent of youths do not have tertiary education and only one per cent of the general population is enrolled in universities.

Last week, students of the University of Benin protested weeks of power outages on the university campus, forcing the management to shut down activities in the school. The students lamented that the prolonged power cut has severely impacted their preparation for their upcoming first-semester examinations.

“We have had only one hour of electricity daily since this issue started. We are tired of studying in the dark. We need electricity to read and prepare for our exams,” John Afolabi, one of the protesting students, reportedly said.

Earlier this month, staff of the Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) Zaria wrote to President Tinubu, seeking his intervention in the electricity crisis bedevilling the institution. In a letter signed by over 40 workers across faculties and departments of the university, noted how the constant disconnection of the university from the national grid by the distribution company poses an existential peril given the centrality of electricity supply to the university’s operations.

In March, Some students of the University of Jos, in Plateau State, locked the school gate in protest over water and electricity scarcity. There was a similar protest at the University of Calabar this month.

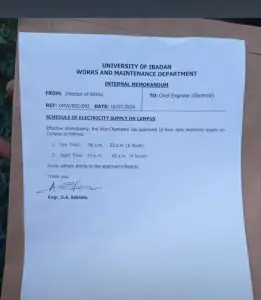

West Africa Weekly also reported that students of the University of Ibadan, Nigeria’s premier university, recently protested over poor electricity supply. The protest was reportedly provoked by the university management’s decision to ration the electricity supply and limit it to 10 hours daily. The students say such rationing is unacceptable as the management had just imposed over 200 per cent increase on tuition fees and sundry levies. They argued that inadequate electricity supply would disrupt their academic activities.

Quadri Yahya, a second-year Linguistics and African Languages student at the University of Abuja, told West Africa Weekly that the university has adopted rationing in electricity supply and described the supply level as “inadequate”. He said the impact is often felt during exams. “Sometimes there’s no light in the night to read.”

Nigerian Universities: Too Poor To Afford Stable Powder

Even though electricity supplies have been chronically poor in Nigeria, federal Universities have had it better, and one of the reasons students prefer staying in university hostels is the stable electricity. However, since the removal of the electricity subsidy by the Tinubu administration, managements of federal universities have said they cannot afford to pay the over 200 per cent hike in electricity tariffs. Even before the hike, many had huge debts, and distribution companies had started disconnecting some of them from the national grid.

The management of the University of Benin said it could not meet the students’ electricity demands after the Benin Electricity Distribution Company (BEDC) raised the university’s bill from approximately N80 million to between N200 million and N280 million. The management’s decision to rely on generators and ration electricity supply sparked the protest that led to the school’s closure.

The immediate past Vice-Chancellor of the University of Lagos (UNILAG), Prof Oluwatoyin Ogundipe, recently lamented that no public university in Nigeria can afford to pay electricity tariffs. The committee of Vice Chancellors of Nigerian Universities has also warned that unless the federal government intervenes by specially subsidising electricity tariffs for them, 52 federal universities may collapse soon.

Meanwhile, the government has refused to improve funding for tertiary education. The electricity crisis deepens educational inequality at the tertiary levels, as students in private universities do not endure such.

Read More:

- Abidjan: Clashes Between Police And Residents Erupt As Neighbourhood Demolished For New Road

- Human Rights Lawyer Inibehe Effiong Writes IGP, Demands Protection of Protesters

About The Author

Related Articles

Zimbabwe Ends Talks on $350m US Health Support Deal

Zimbabwe has formally withdrawn from negotiations on a proposed $350 million health...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 25, 2026Niger’s President Outlines Vision for Strategic Partnership with China

Niger’s Head of State, General Abdourahmane Tiani, has articulated a renewed vision...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 25, 2026Fire Destroys 140 Tonnes of Cotton in Western Burkina Faso

A major fire has destroyed more than 140 tonnes of cotton in...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 25, 2026Mali’s New Ambassador to Angola Presents Credentials, Pledges Stronger Bilateral Ties

Diplomatic relations between Mali and Angola entered a new phase on February...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 25, 2026