“Nigerians Hate Me Like Hell” Then Why Not Resign, Mr. President?

In a country rocking from hardship, insecurity, and daily grief, a statement by President Bola Tinubu has struck a deep chord: “Nigerians hate me like hell.” It is an unusually blunt admission from a sitting president, and one that has ignited fierce public debate.

The question now being asked by many Nigerians is weighty but straightforward:

If you know the people feel this way, why do you insist on staying in office?

It’s not just the words themselves that stung. It’s what they reveal. In those six words, the President acknowledged what millions have been shouting from the streets, market stalls, classrooms, hospitals, and social media. A growing void is emerging between the government and the governed. And that void is no longer just political; it’s emotional and existential. It is a widening wound of disillusionment, frustration, and a sense of abandonment.

A Nation on the Brink

To understand why these words have resonated so strongly, one needs only look at the current state of the nation. Inflation has pushed essential commodities out of reach for many families: fuel scarcity and poor electricity cripple daily life. The naira remains volatile. Youth unemployment has reached unprecedented levels. And across many parts of the country, insecurity, from banditry and kidnappings to militia violence and terrorism, has made everyday life feel like a gamble.

In Benue, over 200 people were recently massacred in a wave of violence that shocked the nation. In Niger State, floods have displaced thousands and left many without food, shelter, or hope. And yet, the federal response has been lukewarm at best, with delayed visits, politicised appearances, and a seeming preference for optics over action.

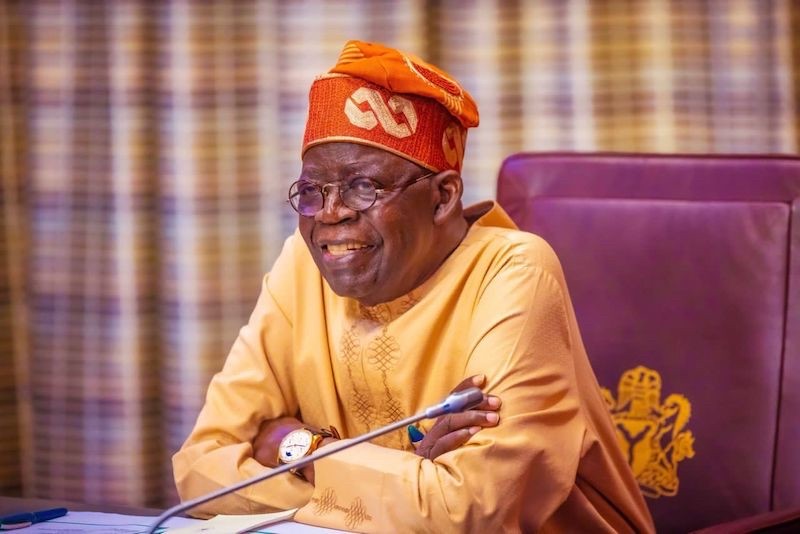

During a condolence visit to Benue, President Tinubu arrived not in sombre attire or humble demeanour, but in full ceremonial regalia. The atmosphere, reportedly festive, included schoolchildren singing rehearsed songs, music, banners, and cheers, hardly the image of a nation in mourning. Some Nigerians, including opposition leader Peter Obi, denounced the visit as a “political carnival,” one that highlighted the disconnect between the ruling elite and the suffering masses.

In this context, the President’s comment that Nigerians hate him feels less like an observation and more like a confession.

Leadership Without Love

Let us be clear: leadership is not a popularity contest. It is not unusual for leaders to face criticism, dissent, or public anger, especially in times of hardship. However, the widespread, deep-rooted discontent currently felt in Nigeria is not ordinary democratic tension. It is symptomatic of a profound failure in leadership, communication, and empathy.

When a president acknowledges that the people “hate” him, it implies more than political opposition. It signals a breakdown in the social contract. And in a functioning democracy, when that contract is irreparably damaged, there are two options:

Rebuild trust or step aside.

Rebuilding trust requires a radical shift in governance. It means listening, not just hearing. It means acting, not just appearing. It means sacrifice, transparency, and a people-first agenda that is visible, tangible, and consistent. Unfortunately, many Nigerians no longer believe that this administration is capable or even willing to make that shift.

So, we are left with the other option: calling for the president’s resignation.

Is Resignation So Extreme?

Some will argue that calls for resignation are premature or dramatic. But is it so far-fetched?

In other democracies, political leaders step down not only when caught in scandal or failure but when they lose the moral authority to lead. British Prime Ministers have resigned after a public loss of confidence. South Korean presidents have stepped aside under pressure from protests. Leaders like Ethiopia’s Hailemariam Desalegn and Mongolian Prime Minister resigned for the sake of national stability.

Resignation, in such cases, is not a defeat. It is an act of grace. It is recognising that leadership is not about clinging to power, but about serving people with integrity. And when service turns into suffering for the governed, choosing to leave can be the highest form of responsibility.

President Tinubu must ask himself: What kind of legacy do I want to leave behind? Do I want to be remembered as the leader who stubbornly presided over a divided, despairing nation or as the one who dared to admit when the people no longer believed?

A Nation Is Bleeding, and We Are Clapping

What Nigeria needs now is not denial, distraction, or deflection. We need vision. We need honesty. We need healing, and above all, we need leaders who understand that occupying the highest office in the land is not an entitlement. It is a duty to serve the most vulnerable with humility and conscience.

When condolence visits become carnivals, when grief is met with pageantry, when hardship is met with platitudes, and when a president admits he is hated but takes no meaningful steps to change course, then we are not just losing trust. We are losing our soul.

President Tinubu still has a choice. He can radically reform his leadership, prioritise people over party, and rebuild broken bridges, or he can accept the reality of public sentiment and step aside to allow new leadership to emerge.

Because this is bigger than one man. It is about a nation desperately searching for direction, justice, and hope.

And if our leaders will not rise to the moment, then the people will, as they always do. A new Nigeria is not just a slogan. It is a call, and one day soon, it will be answered.

To lead a nation is to love its people, and love, when truly felt, never insists on staying where it is no longer wanted.

About The Author

Related Articles

AES Condemns Niamey Airport Attack, Warns of Coordinated Destabilisation

The Alliance of Sahel States has strongly condemned the armed attack on...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Mali Cedes Strategic Land to Guinea to Deepen Trade Cooperation

Mali has approved the transfer of a strategic parcel of land to...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Senegal to Appeal CAF Sanctions After AFCON Final Controversy

Senegal has announced plans to formally appeal the sanctions imposed by the...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Burkina Faso Takes Legal Step Toward Nuclear Energy Development

Burkina Faso has voted to join the Vienna Convention on Civil Liability...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026

Leave a comment