Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Voice of African Literature, Dead at 87

Hope was born. But hope, if it is bold, is bound to be killed. That’s why hope is so painful. — Weep Not, Child (1964), Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o did not merely write books. He bore witness. For over six decades, the Kenyan writer and academic stood at the intersection of literature and liberation, using his words to reflect the trauma of colonialism and the struggle for post-independence identity across Africa. He died on May 28, 2025, in Atlanta, United States, at the age of 87. With him goes a body of work and a generation of thought that refused to separate language from freedom.

The brutality of colonial Kenya shaped Ngũgĩ’s early years. Born James Ngugi in 1938 in Kamiriithu, he came of age during the Mau Mau rebellion, witnessing first-hand the devastating consequences of land seizure, family fragmentation, and cultural loss under British rule. These themes would later form the emotional spine of his first novel, Weep Not, Child, published in 1964, the first major novel in English by an East African author.

But it was not enough for Ngũgĩ to write in English. In the 1970s, he began a radical linguistic and political shift. He changed his name and began writing in his native Gikuyu language, declaring that African literature must liberate itself from colonial languages. This decision was costly. After co-writing and staging the play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), performed by local peasants in Gikuyu and critical of social inequality, Ngũgĩ was arrested and detained without trial by the Kenyan government. He wrote Devil on the Cross while in prison, by hand, on toilet paper.

His refusal to write in colonial languages became his life’s mission. In essays like Decolonising the Mind, he argued that language is not neutral. It shapes culture, defines memory, and carries power. For Ngũgĩ, writing in English, French, or Portuguese was to participate in a form of continued colonisation. He called on African writers to embrace their mother tongues not just as mediums of communication but as tools of cultural survival.

This position isolated him from some global literary circuits but earned him immense global respect. His ideas became foundational in university syllabuses from Nairobi to Accra. He was read alongside Achebe and Soyinka, though he stood apart in his relentless pursuit of linguistic decolonisation. While Achebe famously declared that English could be used to tell African stories, Ngũgĩ remained unconvinced. For him, the recovery of African identity required a full return to African languages.

READ MORE: Caméra d’Or Spotlight Falls on Akinola Davies Jr’s “My Father’s Shadow” at Cannes

Exiled for years and living in the United States, he continued to write and teach. At Yale and later the University of California, Irvine, Ngũgĩ remained outspoken about the failures of African leadership and the complicity of African elites in neo-colonial systems. His voice never softened, even when speaking from abroad. He remained a fierce critic of cultural erasure and a defender of the marginalised.

Ngũgĩ’s death has prompted tributes from around the world. But beyond the condolences and accolades lies a more urgent truth. His passing marks the end of a generation of African thinkers who believed literature could be an act of rebellion. He did not seek fame. He sought freedom. And he believed that freedom began with language.

In Weep Not, Child, young Njoroge dreams of rising above his station through education. But that dream is slowly crushed by the realities of colonial violence and social despair. It is a narrative that mirrors the post-independence African experience — the dream of freedom overtaken by betrayal, repression, and disillusionment.

Ngũgĩ’s legacy is not only in the books he wrote or the ideas he championed. It is in the young African writers today who are returning to their mother tongues, questioning global gatekeepers, and finding new ways to tell stories rooted in local realities. His life was a challenge to the notion that African voices must speak through borrowed tongues.

Now that he is gone, the question remains. Who will continue the work? Who will risk being unheard, unread, and unmarketed to write in the languages of home?

Weep not, child. But remember. For even in silence, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o still speaks.

About The Author

Related Articles

Asake Sets New Billboard Afrobeats Record as Chart Presence Grows

Asake has further cemented his place as one of Afrobeats’ most dominant...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Nigerians Lament PayPal’s Return as Old Wounds Resurface

PayPal’s reentry into Nigeria through a partnership with local fintech company Paga...

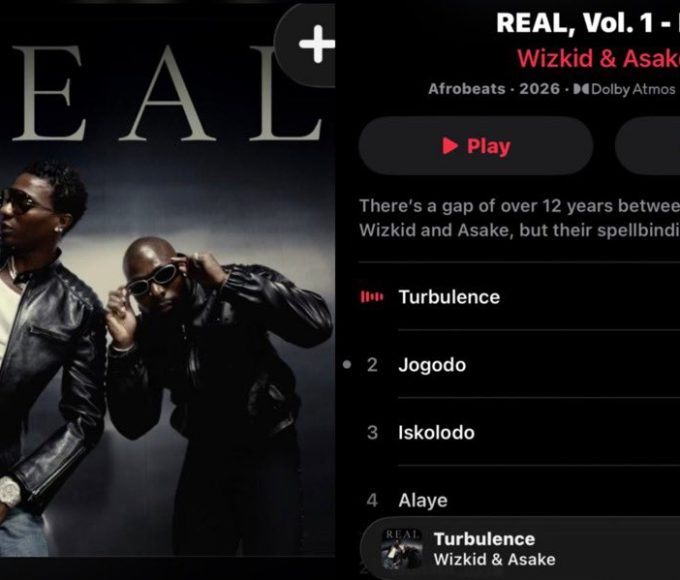

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Wizkid and Asake Join Forces on New Collaborative EP

Wizkid and Asake have released a collaborative EP, uniting two of Nigeria’s...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Tanzania Eyes Gold Sales as Aid Declines and Infrastructure Needs Grow

Tanzania is weighing plans to sell part of its gold reserves to...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026

Leave a comment