When the young filmmaker from southwestern Nigeria, Shittu Abdulafiz Opeyemi, set out to make Dodo Ikire, he wasn’t chasing festival validation or global applause. He was chasing something more personal, the story of home. Ikire, the small Yoruba town from which the popular plantain snack takes its name, had always fascinated him. Its people, its rhythms, and its food culture held a quiet poetry. “Being familiar with the terrain made it easier,” Shittu tells West Africa Weekly. “I understood the people, the everyday life of the place, the rhythm of their lives.”

That rhythm hums through every frame of Dodo Ikire, a short documentary that opens with a traditional eulogy to the town itself. The choice was deliberate. “The music that started the documentary was a way to pay respect to the town of origin,” he explains. “Most of the people making the dodo were from Ikire.” The song isn’t just a prelude; it’s an invocation. From there, the film unfolds through scenes of women peeling and frying plantains, the heat of the oil shimmering in the air, the soundscape thick with the chatter and laughter of the market. The handheld camera lingers on textures, banana peels, bubbling oil, work-worn hands, all part of a visual language that feels lived, not observed.

At first, the project seemed straightforward: a short awareness film about the popular snack. However, the story took a deeper turn as Shittu began to confront a damaging myth spreading through Nigeria, that dodo ikire was made from rotten bananas. The rumour had started to hurt sales and the reputation of the women who produced it. “I realised these women had little capital and no access to mass markets. Lies were undermining their craft,” he says. The film became a corrective, not just to document, but to vindicate.

“The goal was to show that the chain of production was legitimate,” he explains. “Anyone can say, ‘we don’t use rotten bananas,’ but to show the process, from raw material to finished product, that’s visual proof.” He initially planned to shoot for one day, but authenticity demanded more. He spent days following the process, from purchasing fresh plantains at the market to frying and packaging them. The more he filmed, the more he understood that Dodo Ikire wasn’t just about a snack; it was about women’s work, value chains, and cultural preservation.

In the editing room, Shittu worked with clarity and restraint.

I had so much clarity on what I wanted, and I went for it, he says. Scenes that didn’t advance the story were cut, but the essential moments, the frying, the chatter, the laughter, the market sounds, stayed. It’s always tempting to over-edit, but I wanted to keep the truth of the place intact,” he adds.

What emerged was a short film that feels both intimate and expansive, grounded in local detail but resonant with universal themes: women’s labour, informal economies, the dignity of work, and food as cultural identity.

Being the only West African filmmaker selected at the Youth Film Festival of the World Film Forum (WFF), Shittu carried his regional identity into every frame. “It was important for me to show Africa as a system that works, not chaos, not pity, not struggle, but structure and agency,” he says. In Dodo Ikire, the women are not victims of circumstance; they are custodians of a craft. The film reframes Africa not as a reactive subject but as a space of innovation, resilience, and self-definition. “Africa has a clear and defined system of operating at any scale,” he insists. “We just have to show it.”

He hopes international audiences will see that too. “I want people to leave the film not with pity, but with understanding and respect,” he tells West Africa Weekly. For Shittu, representation isn’t about exoticising the local; it’s about expanding the lens through which the local is seen.

His next project, The Grief, which recently screened at several African festivals, takes on another deeply personal theme: how Africans, and Nigerians in particular, process grief.

It’s about how we bottle emotions, and how that affects our healing, he explains. The film, like Dodo Ikire, returns to a familiar tension in his work, the intersection of culture, emotion, and expression. I see this WFF selection as confirmation that I’m on the right path, he says.

Shittu plans to keep telling stories rooted in women’s lived experiences, culture, and food systems while exploring collaborations beyond his immediate environment. “I will keep exploring stories that are original to Africa, while showing how our culture influences our experiences,” he says. “But I’m also looking forward to expanding into new territories and working with other filmmakers.”

At its heart, Dodo Ikire is a love letter to home, to women’s labour, to the small economies that sustain communities, and to the idea that cinema can dignify the ordinary. In crafting this story of plantains, oil, and persistence, Shittu Abdulafiz Opeyemi isn’t merely preserving a tradition; he’s reframing it for the world.

Read More:

- Ghana Launches Sweeping Audit of Mining Firms in Decade’s Biggest Oversight Push

- TikTok Pulls Down Over Half a Million Videos in Kenya as Platform Steps Up Safety Enforcement

About The Author

Related Articles

Sinners Breaks Records as Oscar Nominations Set Stage for Fierce 2026 Awards Race

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has announced the full...

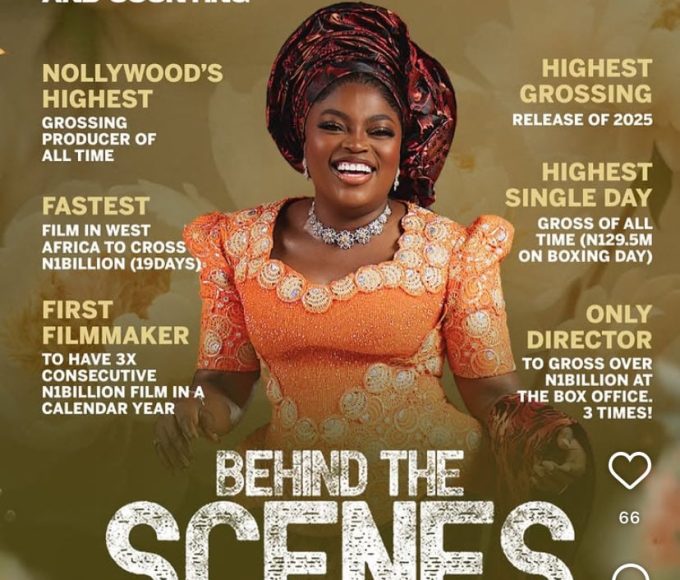

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 23, 2026Funke Akindele Extends Box Office Streak as New Film Hits ₦1bn

Nollywood actress and filmmaker Funke Akindele has set a new box office...

ByWest Africa WeeklyDecember 31, 2025Wizkid, Seyi Vibez, and Asake Dominate Spotify’s 2025 Wrapped in Nigeria

Spotify has released its 2025 Wrapped data, and the results show another...

ByWest Africa WeeklyDecember 4, 2025Lagos Welcomes XVI Edition of S16 Film Festival Featuring Shorts, Features, and Panels

The 2025 edition of the S16 Film Festival officially opened in Lagos...

ByWest Africa WeeklyDecember 3, 2025

Leave a comment