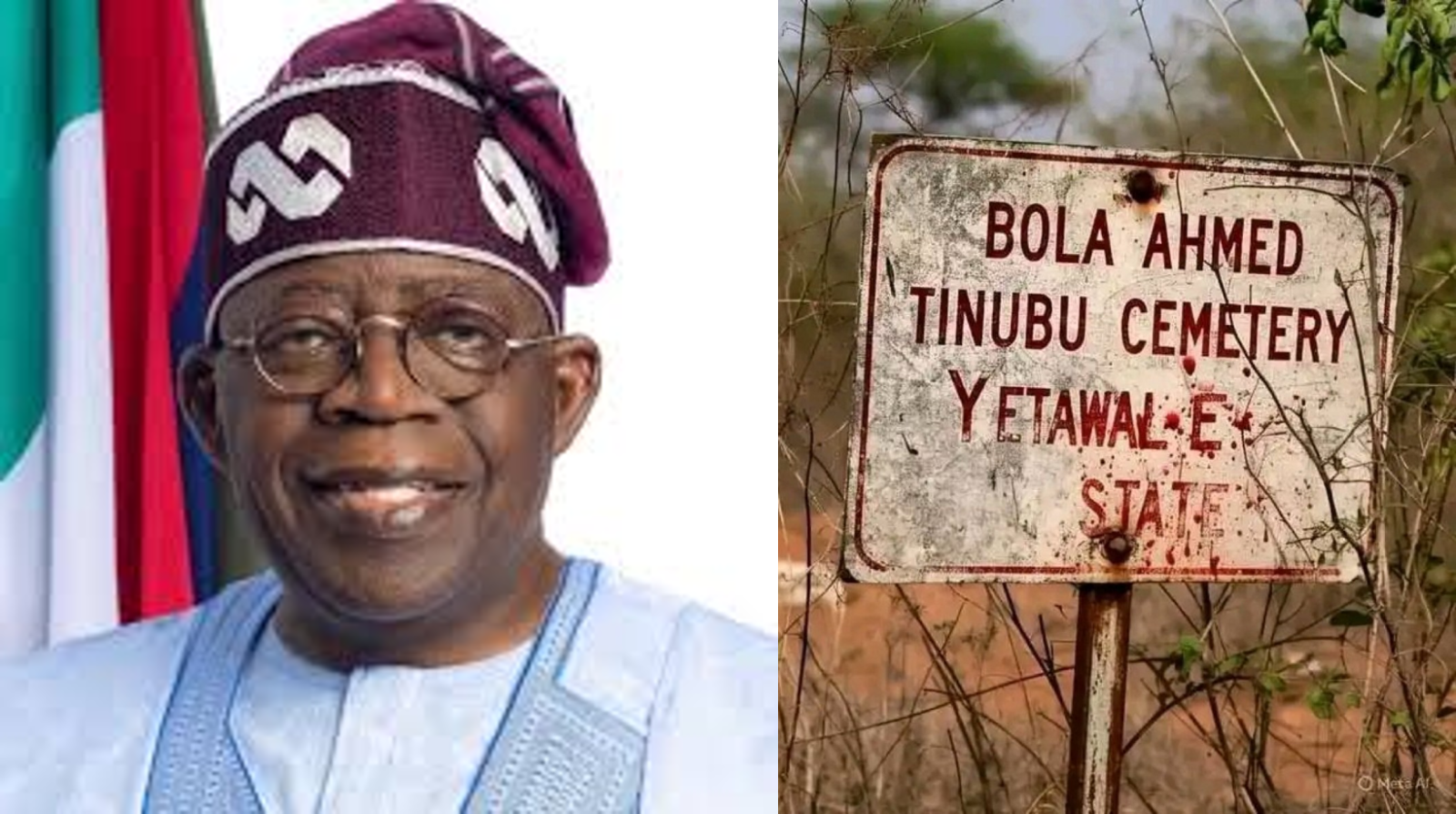

‘Tinubu’ Now Christened on Airports, Barracks, and Possibly Mass Graves

In a country where hunger kills faster than bullets and terrorism has become a national pastime, there’s at least one thing moving at full speed: naming public institutions after President Bola Tinubu.

From airports to polytechnics, libraries to military barracks, and now even the iconic Abuja International Conference Centre, Nigeria seems determined to spell out “Tinubu” in concrete, steel, and marble across the land. One might wonder:

At this rate, will the graves of the dead, those claimed by hunger, flooding, and bullets, be named after him too?

If so, let the headstones read:

“Here lies a Nigerian, victim of governance. Resting on Bola Tinubu Memorial Soil.”

Let’s be clear: memorialising public figures is not inherently wrong. However, it’s typically done after they’ve left office. Preferably after they’ve left a legacy. In most democracies, naming buildings after a leader mid-tenure is seen as premature at best, egotistical at worst. In Nigeria, however, it’s become a national emergency, one of the few things we respond to with absolute urgency.

Seven major institutions and counting have already been renamed after President Tinubu, some within the first 12 months of his administration. That’s one naming per nearly five million citizens battling hunger, according to the Global Report on Food Crises 2025, which projects 30 million Nigerians will face acute food insecurity this year. But not to worry, at least the buildings have names.

While our children are stunted from malnutrition and farmers flee their fields due to bandits and floods, state governors are competing to etch the president’s name onto every square inch of public infrastructure. One governor in Nasarawa recently named roads and healthcare facilities after Tinubu, even though thousands in the state lack access to clean water and functional hospitals. It’s as if these plaques and signage are edible.

You might ask, Where is the president in all this? Has he addressed the flooding that destroyed over 700,000 hectares of farmland in 2025? Has he deployed emergency food reserves for communities in Borno, Katsina, or Benue, where farming has become a life-threatening endeavour? Has he responded to the grim projection that 1.2 million Nigerians could slip into emergency-level hunger this year?

Well, he hasn’t. But his name is on a conference centre.

It’s almost poetic, while displaced persons beg for food and shelter, our leaders gather in halls named after themselves to discuss the economy they’ve gutted. As food prices soar due to the removal of subsidies and naira devaluation, we receive ribbon cuttings and freshly painted signboards in return, while children eat only once a day, if at all.

This is not leadership. It’s legacy theatre.

The symbolism is hard to miss: the more the country burns, the more names we slap on fire stations that don’t work. The more graves are dug, the more buildings rise, with no public input and certainly, no shame. At this point, one expects a national cemetery to be christened the

“Bola Ahmed Tinubu Eternal Rest Park.” A solemn tribute to governance that arrived too late.

Perhaps one day, there will be monuments to the unnamed: the farmer shot in his field, the child who died of hunger, the mother who drowned in the flood. Until then, we’ll continue this naming spree, because when it comes to vanity projects, this administration spares no expense.

Meanwhile, Nigerians are left asking: what good is a name on a building when the people it’s meant to serve are either fleeing, starving, or dying?

At the current pace, you might want to reserve your family plot now as it may soon carry a presidential prefix.

About The Author

Related Articles

Mali Tightens Grip on Explosives Supply With New Majority Stake

The Malian government has taken majority ownership of a civil explosives manufacturing...

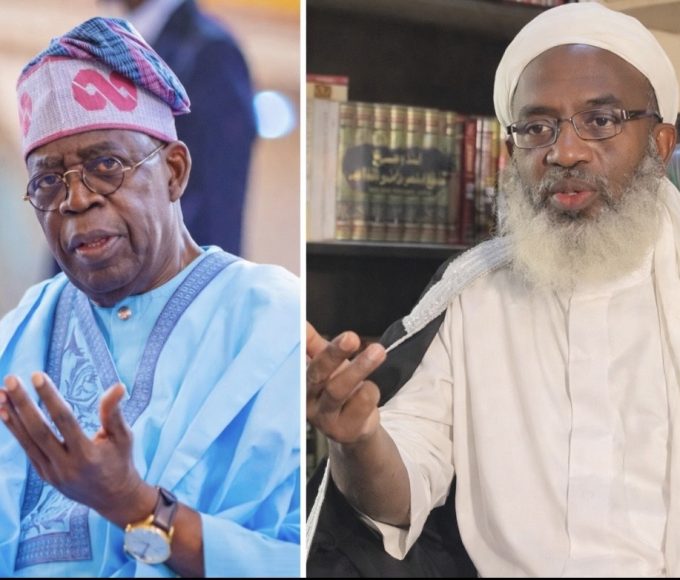

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Tinubu Follows Gumi’s Lead as Nigeria Signs Turkey Defence Deal, Fueling Speculation Over Who Really Controls the Country’s Security Policy

Nigeria’s diplomatic and security strategy is once again under scrutiny after a...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 28, 2026Trump’s Greenland Threat Forces Europe to Taste the Logic of Western Colonial Power

It rarely begins with soldiers. More often, it begins with a sentence,...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 21, 2026Tinubu Government Claims Intelligence Cooperation With the US, Yet New York Times Publishes Conflicting Story Following $9 Million US Lobbying Effort

When the New York Times published its investigation suggesting that claims from...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 19, 2026

Leave a comment