Journalism Career Graveyard: The BBC And Its West Africa Problem

The first thing one learns in this line of business is the maxim “There is never just one cockroach.”

Journalists, private investigators and short sellers are taught to live by this saying as they hunt for information about organisations that do not always appreciate exposure. In his book “Money Men: A Hot Startup, a Billion Dollar Fraud, a Fight for the Truth,” Financial Times journalist Dan McCrum explains how chasing down the single “cockroach” of accounting fraud at Wirecard ballooned in front of his eyes, ultimately turning into a story that involved air gapped computers, secret document pickups in Singapore, a cross-border Russian spy operation, Libyan mercenaries and ultimately a €24bn corporate collapse that rocked Europe’s largest economy.

The problem for a journalist interested in the inner working of BBC West Africa, is an altogether different one. Rather than struggle to identify a single cockroach and then follow its trail to find more cockroaches, one is immediately confronted with what looks like several cockroaches. Nigeria’s media space is not a very big one, and there is never a shortage of whispers about scandals at that organisation. Upon closer inspection however, these “cockroaches” have almost inevitably turned out to be mere hints of cockroach activity. Lots of rumour but little substance. All icing and no cake. Lots of flavour, but little food.

“This person was employed because they are so-and-so’s family member.” “So and so are publicly having an affair even though one reports directly to the other. They even audibly have sex in the office.” “So and so had sex with that and the other to get into a BBC production without having any formal qualifications.” “HR at BBC West Africa is nonexistent.” “So and so is such a bad office bully that they made so and so resign and quit journalism for good.” The gossip and rumours come thick and fast, but invariably, when it is time for anyone to provide documentation or go on record, the are-they-are-they-not-cockroaches disappear, and nothing is ever established.

This all started to change on Sunday, December 13, 2020, when Oge Obi, a broadcast journalist working at the BBC Lagos Bureau decided that she had had enough. Over the course of 2 alcohol-fueled hours, she poured out her angst, referencing the things she claimed to have gone through in the hands of her superiors and the the BBC’s notoriously cavernous hierarchy. Unfortunately, the episode did not end well for her, culminating in a livestreamed suicide attempt that left her in hospital for the next 2 weeks. The BBC subsequently fired her, and to all intents and purposes, that was the end of that.

What the decision makers in Lagos, Dakar and London did not know was that – ill advised as it might have seemed at the time – Oge’s self-immolating act of defiance had started a fire in the minds of her colleagues in Lagos, Abuja and Dakar. Previously, under strict instruction from the organisation, they would never dare to speak publicly about their experiences – even after leaving the BBC. Now however, having witnessed the near-death of their colleague, they were finally ready to do away with their silence. For the first time ever, current and former BBC Africa employees and contractors started to reach out in numbers to those they believed could tell their stories. I was one of such people.

The following 3 stories, taken from extensive testimonies and documentation provided by BBC Africa staff in Dakar, Abuja and Lagos, are the culmination of nearly 2 years of research and interviews. On an individual basis, they paint the picture of an organisation with huge gaps in corporate governance and a massive HR malpractice problem. Taken from a wider angle, they form part of the bigger picture of a dysfunctional British public institution that according to some, shouldn’t even exist in its current form. While it suffers from the same intractable internal governance problems at home, nowhere are these failings more greatly magnified than at its weakly-regulated outposts in West Africa.

Our journey begins in Dakar, Senegal.

The American Editor From Hell

“Since her inception as BBC Afrique Editor on October 8th 2019, an alarming number of journalists have left the BBC in order to preserve their mental health. She thrives on resorting to bullying and harassment to force people she dislikes out of the BBC [especially] any journalist who generally does not feel indebted to her.”

Zaïnabou Mohamed Hassane was a freelance journalist who started on the way to what she thought was living her dream in 2019. Ahead of the presidential election in Senegal, the BBC’s Dakar bureau, which was then without an office head, took her on to cover the polls as a freelancer. She later got the opportunity to apply for a full time role at the bureau and she took it. After making it past all the application stages, she received an invitation to a final interview round to be conducted by a board made up of 3 people – the new BBC Afrique Editor, Anne Look Thiam and Senior Broadcast Journalists Godlove Kamawa and Claude Foly.

Describing what happened next, Zainab said:

So, come the day of the interview, I arrive and I was waiting in the newsroom for my turn. When the time came, it was Mrs. Anne who came to call me herself. Just before entering the interview room, she asked me a question which had no connection with the interview. “Were you the one who worked at Ouest TV?” I said yes. “Do you know Coumba?” I answered yes. And there, alas, it clicked in my head, I said it’s over. I’m not going to succeed in this interview, everything is sealed.

I specify that Mrs. Anne saw me every day in the editorial office and knew what I was doing as work for the elections and she never stopped me to ask me if I knew the lady in question. It was on the day of the interview that she asked me about her. Then 10 days later, I got the answer that I was not selected. I asked myself the question several times: why did Mrs. Anne ask me that day if I knew this person? What did that have to do with the interview? There were a lot of questions running through my head. Did I fail because I was not up to it? Or is it simply related to Anne’s question about this Coumba? Who knows.

Unknown to her, what she had stumbled into was the epicentre of the Dakar Bureau’s corporate governance black hole. It would later emerge that “Coumba” was not only one of Anne’s closest friends, but was in fact married to Ouzin Ndiaye, a close friend of Anne’s husband, Charles Thiam. And – get this – Anne had supervised the hiring of Ouzin as a video journalist at the Dakar Bureau. Conflict of interest be damned.

Even more incredibly, she had supervised the hiring of one Hamet Fall Diagne, a close friend and former roommate of her husband, as a Senior Broadcast Journalist. Mr. Diagne, by the way, had no formal qualifications and his greatest career highlight up until that point was directing the first ever web series in Senegal to be filmed entirely on a smartphone.

Somehow, he went directly from this to becoming an SBJ at one of the world’s largest media organisations, and no questions were asked. To put this in its truly ridiculous perspective, Ruona Meyer who headlined the Emmy-nominated 2018 BBC Africa Eye “Sweet Sweet Codeine” documentary was a BBC Africa SBJ at the time. Yet despite clearly being at a more advanced career stage and at a different skill level to Mr. Diagne, they would both apparently share the same job title and seniority level in the same region of the same organisation.

If this sounds suspiciously like the sort of corporate governance shenanigans and HR malpractice that abounds at thousands of mom-and-pop SMEs from Dakar to Ouagadougou, that’s because that is exactly what you are looking at. At the BBC Dakar Bureau, you see, Anne Look Thiam’s word is law. Zainab would later find out that because she had a preexisting feud with Anne’s good friend Coumba, she was never going to get the job. From the moment she confirmed that she was Zainab from Ouest TV, the same one who had beef with Anne’s friend, that door was already closed.

Corporate governance and conflict of interest be damned.

The following comprehensive complaint about Anne Look-Thiam’s Jean-Bédel Bokassa tribute act was submitted earlier this year. In it, Mrs. Look-Thiam’s habit of descending into screaming fits and ordering staff around at the Dakar bureau were detailed. There are no prizes for guessing what the BBC did with this information. The same thing it always does – nothing.

Absolutely nothing.

I got my hands on an email exchange and a few pay slips that confirm the vast salary discrimination that takes place at the Dakar Bureau. In the exchange below, Rose-Marie Bouboutou, a Senior Broadcast Journalist complains that her salary offer as an SBJ is up to 25 percent less than the average for an SBJ in Dakar. No explanation is volunteered for this inexplicable disparity.

In addition to being unjustifiable, this, it turns out is also illegal under Senegalese law. Not that Senegalese law matters especially much to the Anne Look-Thiam regime, as former BBC Afrique journalist Jacques Matand Diyambi found out. In November 2019, Diyambi conducted an interview with Charles Onana, author of the book “Rwanda, the Truth about Operation Turquoise: When the Archives Speak.” Onana is considered an enemy of state in Kigali for his views on the 1994 genocide, which contradict the official version of history.

In February 2020, Anne Look-Thiam fired Diyambi, stating on his dismissal letter

“We have established that your actions were clearly contrary to BBC editorial policy and that you took the initiative to conduct an interview on a controversial subject without following the necessary rules and without referring the matter to the necessary officials. Our request for explanations was in response to the Rwandan government’s complaint about the interview you conducted with Charles Onana. The Rwandan government accuses the BBC of being unfair, biased and inaccurate and has indicated that it reserves the right to take sanctions against the BBC.”

There were 2 obvious problems with this. First of all, the mere accusation of bias and threat of sanction by a regime that is hardly a shining light for press freedom even by African standards, has never been enough to fire a journalist. Second, even if the journalist in question did in fact violate ethics to the point of being sacrificed to appease the Rwandan regime, the Kagame regime itself then denied having ever made a complaint in the first place. So why exactly was Diyambi fired?

The Dakar Labour Court posed the same question to the BBC, and got no satisfactory answer. Consequently, the court ruled that there was no evidence that Diyambi had made a professional error, which made his termination an “unfair dismissal.” The BBC was ordered to pay 10 million CFA in compensation to Diyambi. His response to the verdict was very telling.

“Of course, I would never return to the BBC after the treatment I received, but I am always passionate about my work.”

Peter And The Wolves

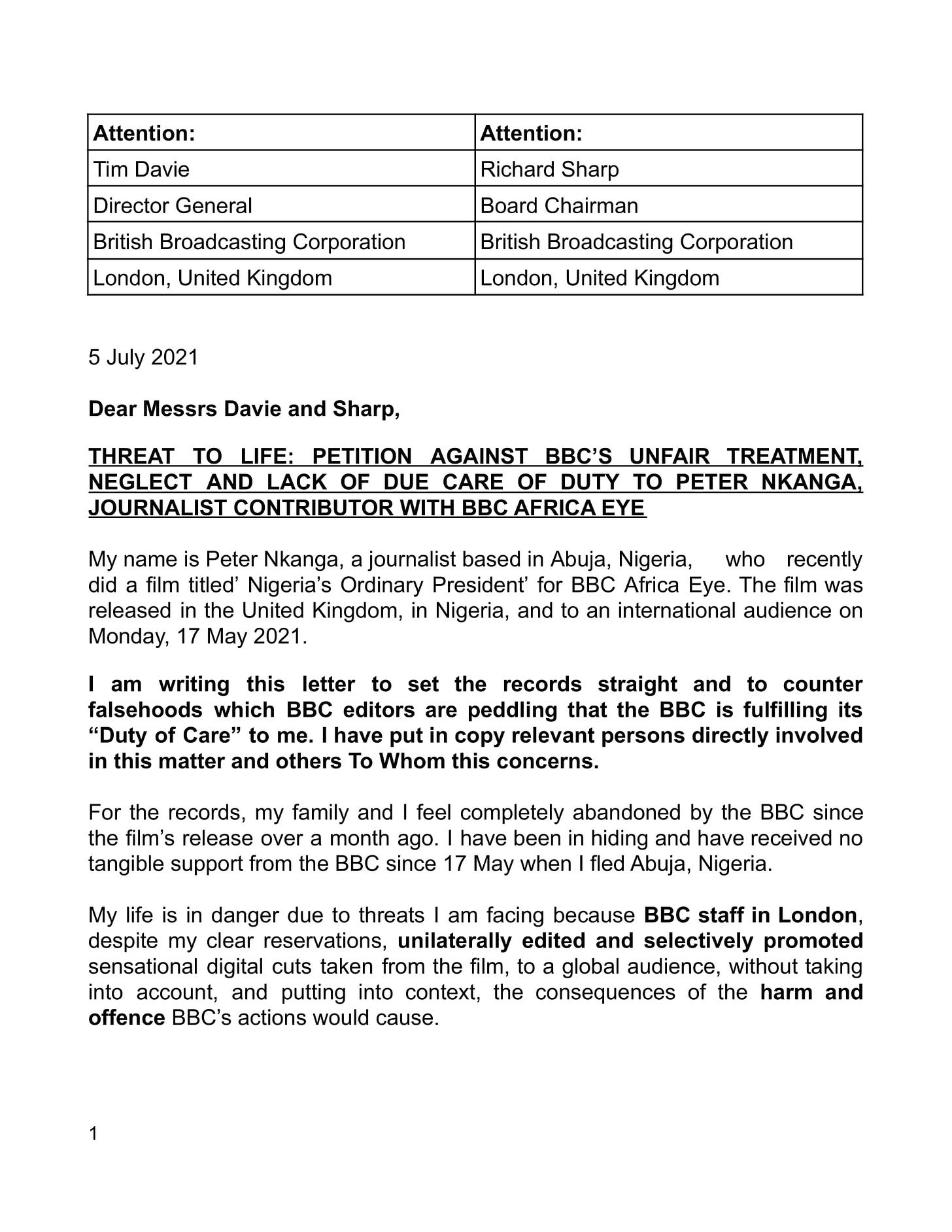

“My life is in danger due to threats I am facing because BBC staff in London, despite my clear reservations, unilaterally edited and selectively promoted sensational digital cuts taken from the film, to a global audience, without taking into account, and putting into context, the consequences of the harm and offence BBC’s actions would cause.”

In May 2021, a BBC Africa Eye documentary called “Nigeria’s Ordinary President” was released. Presented by Peter Nkanga, a BBC stringer, the documentary profiled the methods of Ahmad Isah, the controversial talk show host behind Brekete Family on Abuja’s Human Rights Radio 101.1FM. Its primary purpose was to examine how Isah gets the results that inspire his fanatic following, and to analyse how private individuals like him – for better or for worse – are filling the gaps left by Nigeria’s highly inefficient justice system.

Or at least, that was the documentary that Peter shot.

The documentary that premiered on May 16, 2021 was something completely different. Speaking to me, Peter stated that despite his insistence on being part of the editing and post-production in London, the BBC refused, and left him entirely out of that process. The result he says, was a documentary that focused attention on sensational cuts, such as the infamous scene where Isah slapped a woman, while almost completely failing to deliver on its actual premise.

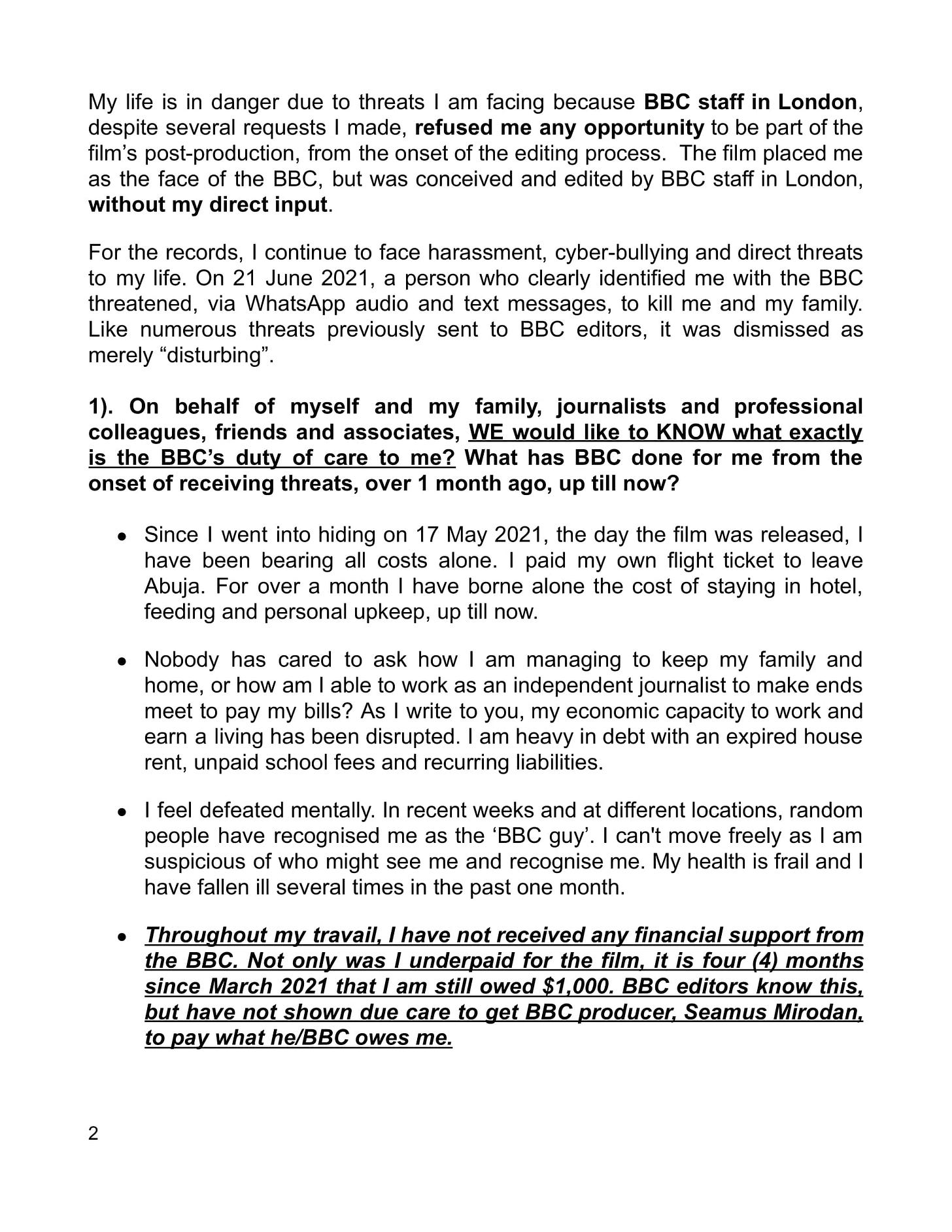

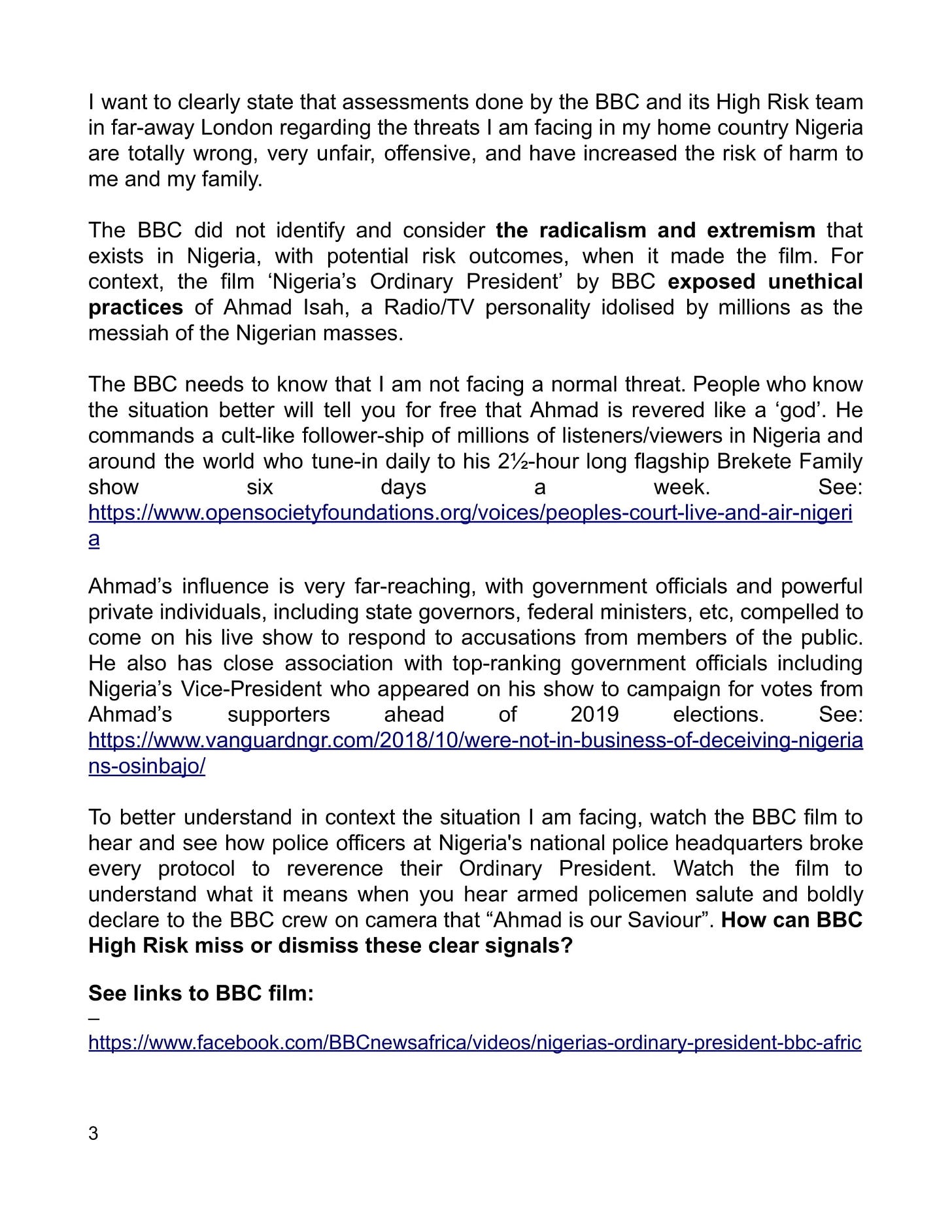

What happened next became a nightmare that Peter has still not woken up from almost 18 months later. An enraged Ahmad Isah, feeling as though he had been set up by Peter – someone he knew personally and had worked with previously – promptly went on air and accused Peter and the BBC of plotting to kill him. In a rambling series of accusations, Isah accused Peter and the BBC of collaborating to destroy the image of Africa, and even trying to honeytrap him using Peter’s wife.

Peter’s personal phone number was also put out but – conveniently – not by Isah himself. Speaking to me a few weeks ago from an unknown location where he remains in hiding, Peter made a wry remark along the lines of “It’s all well and good including “the BBC” in that accusation, but “the BBC” is not a person that can be targeted. Peter Nkanga is.”

For a radio host commands the level of dedicated followership that Ahmad Isah does, this was the same thing as declaring a fatwa on Peter. The radio station’s operating licence would be temporarily suspended a few days later, but by then the damage had been done.

Amidst the 6-lane highways, wide streets, cookie-cutter suburbs and general newness of Abuja, there are very few hiding places for a journalist who just had the largest of targets placed on his back by a celebrity radio host whose primary constituency is drivers, security guards, cooks, street traders and cleaners – all of whom are fanatically loyal to him. To put it in proper context, there would be greater chance of successfully hiding from the police than of escaping detection by Isah’s volunteer network of dedicated followers across Nigeria’s capital.

Peter needed to get out of Abuja – and fast. So he did what any BBC journalist in a dangerous situation would do – he reached out to the BBC and requested help with temporarily relocating his family out of harm’s way. The BBC responded with an offer to house the family temporarily in a hotel under his wife’s name. He pointed out that this was a nonsensical idea, since his wife was just as known as he was. His counter-offer was to use a friend’s name to book the hotel room so as to avoid leaving any records that could be used by Ahmad Isah’s followers. The BBC declined, insisting that he should use his wife’s name or it would not pay for the hotel accommodation.

“Nigerian authorities must promptly and thoroughly investigate the threats made to BBC journalist Peter Nkanga and ensure his safety,” said @angelaquintal. https://t.co/CgXiYbYCLq

— CPJ Africa (@CPJAfrica) May 31, 2021

Getting desperate and frustrated at the BBC’s intransigence, Peter reached out to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) with his predicament. The CPJ put out an alert followed by a couple of tweets about it. A contact at the CPJ then informed Peter that the BBC had reached out to her asking to stop posting about Peter Nkanga, ostensibly to protect its own reputation. Peter Nkanga and his family could end up as Ahmad Isah’s roadkill for all the BBC cared – just don’t post anything that could make it look like it was not protecting its journalist – which it wasn’t.

Ignoring the hundreds of threatening messages pouring into Peter’s phone and social media mentions from enraged followers of a budding cult leader whose tail they had stepped on, the BBC’s Tom Watson and Marina Forsythe insisted that Peter was in no real danger. He was only being a bit of a drama queen, you see.

In a subsequent petition sent to London, Peter expressed his frustration at how the entire problem was created by the BBC’s Africa Eye team, which then outsourced the consequences of its own decisions to him. To add insult to injury, the BBC even went on to owe Peter the balance of his project payment for over one year afterward.

The legendary London-based law firm Schillings found enough merit in Peter’s case to take it on pro-bono, and its legal opinion available in full here, lays out in plain English, the extent to which BBC Africa has violated its own internal guidelines and displayed an utter lack of direction, corporate governance and leadership

To date, Peter remains in hiding, separated from his family for their own safety. The weirdest part of all this, he tells me, is that Ahmad Isah knows very well that he never set out to cause him any harm. All of this, he says, is a complex act set up by Ahmad to protect his image as a powerful saviour. Whereas his hundreds of thousands of loyal foot soldiers believe that Ahmad solves people’s problems, Ahmad actually solves a few people’s problems, and then goes to town with the 1 success story out of every 15 cases brought to him. The other 14 never get followed up on or receive any subsequent coverage.

Peter’s big crime in Ahmad’s eyes, was not being the face of a documentary that showed him slapping a woman. Peter’s crime was actually being the face of a documentary that showed Ahmad as he truly is – a self-promoter who goes back on his word after loudly making promises, and a man is not as powerful as he makes himself out to be. For someone who may be planning a run for public office in future, there can be no worse fate than being demystified.

BBC Africa meanwhile, continues doing what it does best – complete and utter silence. In one of our recent conversations, Peter remarked:

“It feels like the BBC would prefer for me to just disappear. They would like for me to just go away somehow.”

A Journalist, a Documentary and a Suicide Attempt

“Hello David. Toyosi has been also harassing male staff in Dakar bureau. She was sleeping with a BJ Godlove Kamwa from Cameroon. She managed to appoint him SBJ. The guy finally left when the staff learned that they were sleeping together. He is now in Canada. Another Cameroonian guy who was the editor of the French service, BBC Afrique also left because of her harassment.”

Toyosi Ogunseye is many things to many people. To most people, she is a former Punch News editor who was hired to head BBC West Africa in 2017, and the current vice president of the World Editors Forum. To a reliable source that did not agree to be named, she is a social climbing opportunist who had a child for the (married) Chairman of Punch Newspapers, and rose around the same time, to become its youngest-ever editor at 31 years old, which was a remarkable coincidence. To her good friend Samuel Olatunji, the story is a bit different.

I suppose we will never know. But I digress.

To Oge Obi referenced at the outset however, Toyosi is one thing and one thing only – a workplace bully and a ruthless career saboteur. In over 2 hours of exclusive testimony – the first time she has spoken to the media since “the incident” on December 13, 2020, Toyosi’s name came up over and over again – and never for anything positive. The story was not much different with everybody else who agreed to speak to me, with the key difference being that only Oge was willing to go on record with her story about working with Toyosi. And I mean literally on record.

Several other sources such as the person in the quote at the start of this subheading (a current staff member at the BBC Dakar bureau who cannot be named for obvious reasons) spoke of Toyosi in near-identical terms – a connoisseur of office politics, an avid practitioner of the sexual harassment arts, and an all-round nasty piece of work. Long before this story emerged in fact, following several ignored internal complaints, staff at both Lagos and Dakar bureaus co-authored and submitted a petition about Toyosi’s behaviour to the BBC Board – and as usual, radio silence.

BBC Lagos/West Africa Update.

After 9 days , over 200 messages and numerous telephone conversations in odd hours of the day especially at night to protect the identity of my sources, I've forwarded a Petition to the BBC Board.

I intend to refer this petition to the appropriate pic.twitter.com/rQL2XiOsrD

— Baron Chymaker.𝛑 (@chymaker) April 2, 2022

The story of how Oge’s 4-year sojourn at BBC Africa ended in hysterical tears and a downed half bottle of Bifenthrin cannot be told without telling the story of Toyosi’s impact on BBC Africa, starting almost right from the moment she joined in 2017. The 3 other sources I spoke to did not agree to be named, and they all had different perspectives on the things that took place at the Lagos Bureau between 2018 and 2021. All 4 however, agreed on one thing:

The problem, according to them, was not that Toyosi and Ehiz were having an affair, despite Ehiz reporting directly to her. The problem was with how open, careless and blatant it was. Multiple times, there would be public displays of affection in full view of other staff. Often, the company expense card would be used to book a hotel room nearby. On more than 1 occasion, a staff member would walk in on them in a compromising position on company premises.

Now while 2 adults having a consensual relationship is hardly a crime, the reason this is such an important detail to this story is that it sets a backdrop for the consistent problem the reader would have noticed across these stories about BBC West Africa – a complete absence of basic respect for rules and corporate governance. This is not a fast-growing startup with 30-something year-old founders struggling to learn how to manage an organisation, remember. This is the British Broadcasting Corporation – with all of 100 years behind it.

It also paints a picture of the type of human being that Toyosi Ogunseye was – a presence so terrifying that only 1 of 4 ex-BBC Lagos staffers quoted in this story would agree to let their names go on record.

Reporting directly to her at the time was Juwon Soyinka, who headed the BBC Pidgin team. Working directly under him in 2018 was a fresh-faced 24 year-old new hire called Oge Obi. One day, an SBJ called Nduka Orjinmo decided to task Oge with some research for a possible story about sexual harassment of female students by lecturers at Nigerian universities. This is where our story begins.

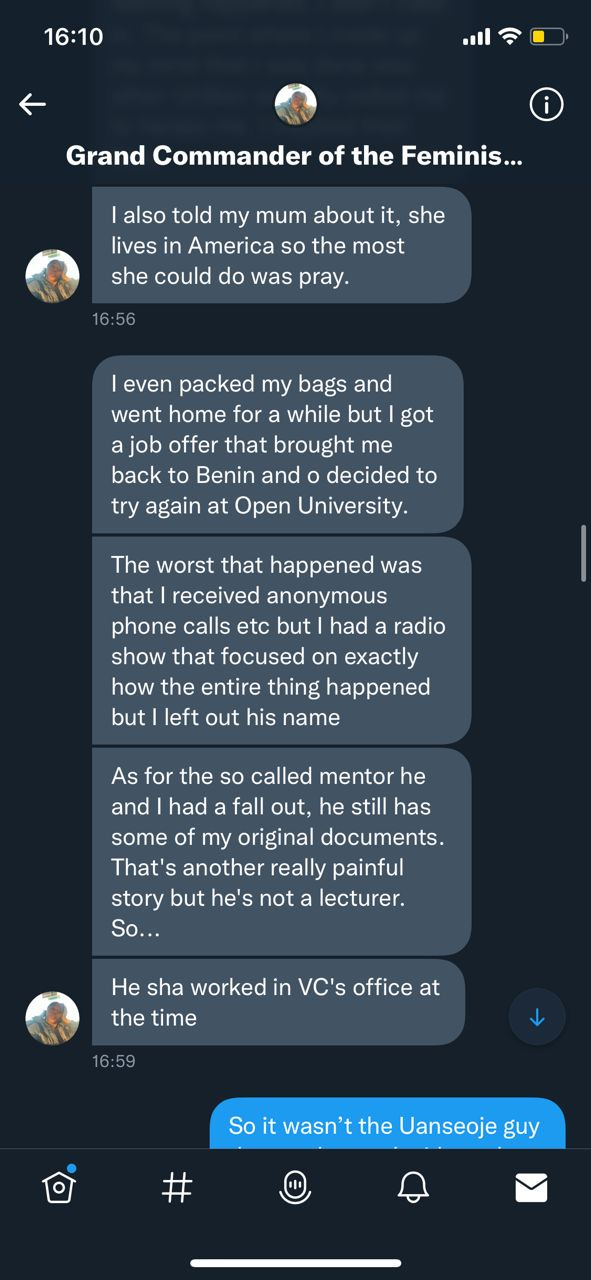

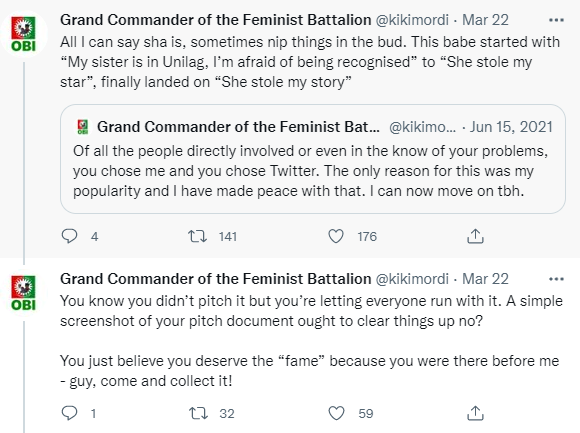

Unable to find the information she was looking for within her personal circles, Oge then decided to tweet a journo request asking for people with experiences of such harassment to reach out. One of the responses to Oge’s tweet came from a little-known radio OAP called Kiki Mordi. Not sure whether Kiki had a story to tell or not, Oge sent her a DM and the following exchange ensued:

From the above exchange, it should be very clear what the situation was – a journalist reaching out to a potential source to ask for more information. That was all there was to it. A story idea mooted by an SBJ. Research work on the story delegated to his direct subordinate. The subordinate juicing her social networks for the desired information. It could, and probably should have ended there.

Until Charlie happened.

Charlie Northcott.

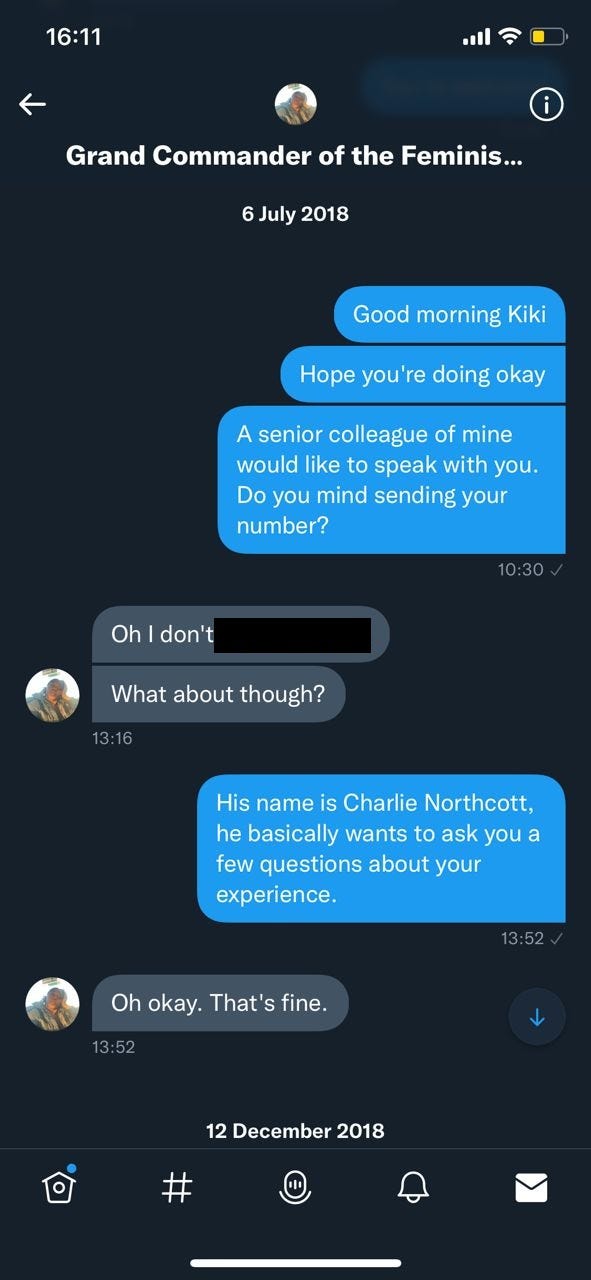

Once listed on a Forbes 30-Under-30 list for his filmmaking work, Charlie is a fixture within the BBC Africa Eye documentary team, and it just so happened that he was in town around this time. Oge’s editor Juwon happened to mention the story she was researching to Charlie, and his ears perked up. Having just finished shooting “Sweet Sweet Codeine,” he was on the lookout for his next investigative documentary in Nigeria and this looked like perfect material. He was introduced to Oge and he quickly tasked her with finding enough information to enable him draw up a pitch to the Africa Eye team.

Soon the list of prospects to be interviewed about their experiences was whittled down to just 2 people – a lady called Diamond Hope Kingston and Kiki Mordi. The idea was to bring them in, thoroughly debrief them, and see what part of their stories could be used as a narrative supplement for the documentary. Diamond, Oge says, opted out of speaking on camera, which left just Kiki even though both she and Charlie felt Diamond’s story was stronger.

Shortly after this, Charlie then informed Oge that she was now in charge of the project since Nduka no longer wanted to be part of the project even though he came up with the story. To this end, he began including Oge in conference calls with senior members of the Africa Eye team and giving her more responsibility. There was only one problem – Charlie was lying, and not for the last time. Nduka never said or inferred that he wanted to withdraw from the project. Keep that in mind because it becomes more important later.

Over the next few weeks, Charlie would proceed to fill Oge’s head with several promises and dreams of journalistic achievement. To a 23 year-old barely 2 years out of school and a few months into a big job at an international media organisation, it might as well have been Jesus Christ talking. Oge believed every word that came out of Charlie’s mouth, and that also becomes a recurring theme in this story.

In addition to the thrill of undercover investigative reporting for someone who always dreamed of becoming a journalist, the story itself hit close to home. At the time, Oge’s 16 year-old sister was herself a student at UNILAG who was being hit on by a lecturer old enough to be her father. This was the story that would make a difference finally. She was sold on it and Charlie knew that he had found someone who would run through brick walls for him.

Toyosi however, had other ideas. Under the BBC’s confusing corporate structure, the Africa Eye team had to take permission from editors and line managers to borrow their journalists. Having seen Juwon receive credit as an executive producer for the Emmy-nominated “Sweet Sweet Codeine” documentary, Toyosi wanted in on the action. The Africa Eye team however, was having none of it due to her closeness to the Vice Chancellor of UNILAG. And thus began an office tug-of-war that would eventually culminate in disaster.

If the reader is following and wondering how come an organisation like BBC Africa has no clearly defined guidelines or processes for dealing with issues like this, then that is exactly the point – BBC Africa apparently, is Oxford Street on the outside, but Jankara Market on the inside. A mess.

But I digress.

It was time for undercover recording training and for some unspecified reason, Kiki had been included in the team. Bear in mind that she was neither a filmmaker nor a journalist of any significant repute. She was a witness/victim brought in by the lead journalist on the documentary to say a piece-to-cam and go home. What happened that altered her contribution to the project from that of a radio host recounting an experience on camera to an “investigative journalist” (with zero prior research or investigation experience) working on a groundbreaking Africa Eye documentary in the space of a few days remains unclear. If this sounds eerily similar to the Anne Look-Thiam situation in Dakar, then you’re getting the picture.

I put the question to Charlie himself, and in classic Charlie fashion, he tried to weasel his way out of giving an answer by responding with questions.

Perhaps Charlie may not remember being in a position where he could influence who got to play what role, and he should be given the benefit of the doubt. Oge however, does remember being the person who was used to do the actual work that the other 2 “undercover reporters” – one fresh out of school and the other a bit older, but with basically the same amount of journalistic experience as the first- could not do.

For example, the infamous “Cold Room Experience” scene – the scene that made the entire documentary – was Oge from top to bottom. I developed actual chills when she recounted the experience to me, and that is why I think you should hear it too. It really is something.

Oge also remembers that as soon as this was done and there was a finally documentary worth editing, things rapidly started to change. First of all, it suddenly became impossible for her to take part in the next leg of the investigation, which included trips to Benin and Accra. The “Toyosi doesn’t want you on the project,” which hadn’t stopped them from working for several weeks, suddenly became an insurmountable obstacle.

“Never mind,” Charlie said. “This is your story, Oge.” She would go on to hear that phrase multiple times from Charlie over the next few months as he assured her that the rug was not being pulled from under her feet, while the evidence of her eyes said otherwise. “This is your story.” “You led this investigation.” “Don’t worry about it! You’ll get your credit!”

She had brought in someone from Twitter to recount a personal experience in front of a camera. Somehow, this person had finagled their way into being part of an investigative production they were not qualified to be on, and could not produce any valuable undercover footage from. Despite having clearly taken a back seat during the actual risky hard work of undercover filming, this person was now apparently supposed to fly to London to voice the documentary. “You’re going to London too,” Charlie assured Oge. And then this happened.

Even more perniciously, Oge explains, Charlie then informed her that due to “security concerns,” she would not be allowed to have her face or name shown in the documentary. The “security concerns” in question referred to a conversation she once had with Charlie where she asked how the BBC would protect her sister who was then a student at UNILAG, when the documentary came out and implicated a UNILAG lecturer.

The BBC’s answer to this at the time was not to offer any kind of logistical support for moving her sister out of harm’s way. It was to carry out a social media sweep and basically make her an internet ghost. Incensed by this utter non-solution to a real potential problem, Oge and her mom had in fact already made arrangements to fly her sister out of Nigeria to continue her education in Europe. None of this was the concern of Charlie or the BBC until it was time for Oge to appear on camera. Then suddenly, “security concerns” materialised out of nowhere.

At this point, Oge was given a choice to either accept this enforced anonymity that she did not want, or have her work taken out of the documentary. Even at this point she says, despite having realised the good-cop-bad-cop game Charlie and Toyosi were playing, she still thought that the story was more important than getting her due credit, which was why she grudgingly consented to the arrangement. Without the “Cold Room Experience” scene and her other captured footage, there was no documentary to speak of.

In hindsight she says, she regrets that decision.

When poking around to research this story, I remembered that I had once bumped into a tweet by Tom Saater, a filmmaker friend of Charlie, which hinted at an abnormal closeness between Charlie and someone brought in by his reporter to be a waka pass. Very tellingly, as soon as I interacted with the tweet and queried this closeness, Tom Saater immediately deleted it, but not before I got screenshots.

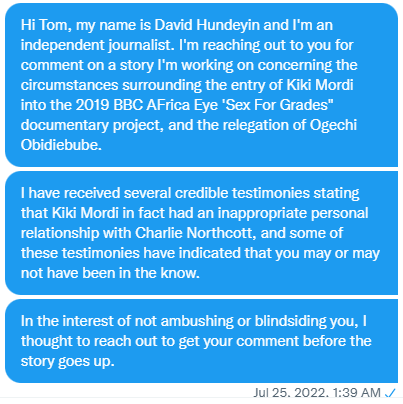

I reached out to Tom a few weeks ago to get his side of the story. Predictably, this was what came back

Oge however, has a very different recollection of Charlie. In our lengthy conversation, she recounted listening to Charlie inadvertently reveal that he had visited Kiki at home by talking about playing with her pet cat. Immediately he said it, he tried to cover it up with a joke she remembers, but the inference had already stuck. She also recalls him confiding in her one day about having had sex with a coworker.

Whether Tom actually knows his friend as well as he says he does is immaterial to Oge, because the evidence of her eyes already told her everything she needed to know. In the clip below, she describes walking into Kiki and Charlie The Faithful snuggling up to each other during an evening event at Alliance Français in Ikoyi, Lagos. One of the people in this paragraph has definitely been telling lies, but it’s up to the audience to judge which one. I know who my money is on.

In any case, Oge is quick to point out that she no longer cares about who believes or does not believe what. After the cruelty she experienced in December 2020 she says, nothing really moves her anymore.

All that matters she says, is that her story goes on record, so that the misinformation that has been peddled for years will not someday solidify into fact. The only frustration she feels is with her former colleagues, including many who have left the BBC, who refuse to speak up as though they are in a “cult.” In her words,

“Other people were there during these periods and they saw these things happen. I’m not a crazy person. It’s just a shame that people are too cowardly to speak up, as if the BBC is some kind of monster that will hunt you down and kill you in your bed at night.”

Right now, she says, the reason she has finally decided to put her story out and set the record straight is because BBC Africa inadvertently freed her from the yoke of fear by taking everything away from her. The promising BBC career, the groundbreaking Emmy-nominated documentary that she did the actual work on, any future as a journalist – they took it all away. And all she got out of everything was an insulting N5 million ex-gratia payment and a certificate to say, “I am the masked “Kemi Alabi” from ‘Sex For Grades’.”

When I ask her what her major takeaway was from all that happened at BBC Africa, Oge does not skip a beat before replying:

“You need to know when you have the upper hand and hold those in power by the balls. Because if the tables were turned, trust me, they would do what is in their best interest. Always do what is in your best interest.”

Anne Look Thiam was quietly hooked from her role as Editor at BBC Afrique shortly before this story came out. She has now been parked in a comfy, nondescript new role in Washington DC.

Marina Forsythe has left her job issuing statements at the BBC and moved on to a new role as a Public Relations Manager at Sky.

Tom Watson retains his role as head of BBC Africa Eye. He has faced no questions or disciplinary action for his role in the Peter Nkanga debacle.

Ahmad Isah continues to hold court in Abuja. He has never tried to stop his followers from harassing Peter Nkanga and his family.

Charlie Northcott retains his job at the BBC. He has never faced so much as an internal panel of inquiry.

After disrupting multiple careers, publicly conducting a workplace affair with a married subordinate and contributing to a suicide attempt by a staff member, Toyosi Ogunseye was moved to London and promoted to the role of Senior News Editor for News and Commissioning.

After publicly conducting a workplace affair with his superior, Ehiz Okharedia was promoted to Head of BBC West Africa.

3 years after, Kiki Mordi continues to claim ownership of the Sex For Grades documentary. She has achieved nothing of any note since then.

Since publicly goading a suicidal Oge Obi to go through with it, Sandra Ezekwesili has been promoted to Group Brand Manager, Nigeria Info FM.

Rose-Marie Bouboutou has left journalism and now works in Communications.

Peter Nkanga has lost interest in journalism and just wants his life back. He still receives threatening messages regularly.

Oge Obi made a near-miraculous full recovery. She has left journalism and now works in Communications

About The Author

3 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related Articles

CSS States Considers UEMOA Boycott Over Alleged President Ouattara’s Power Rotation Block

Tensions are rising within the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA)...

ByOluwasegun SanusiJuly 9, 2025Sanctuaries or Stages? How Politicians Are Hijacking Nigeria’s Religious Spaces

In a nation where faith holds deep cultural and spiritual significance, Nigeria’s...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJuly 6, 2025Atiku, Obi, El-Rufai, Others Adopt ADC as Coalition Platform Ahead of 2027 General Elections

A coalition of opposition figures, including former Vice President Atiku Abubakar, ex-Kaduna...

ByOluwasegun SanusiJuly 3, 2025Gilbert Chagoury: The Convicted Money Launderer Behind Tinubu’s Global Image and Domestic Ambitions

As President Bola Tinubu’s administration deepens its grip on Nigeria’s public institutions,...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJuly 2, 2025

This is really a great read David, so revealing! The world is not fair and unfortunately ths fools and liars hide in high places… What I know and believe is that what we do in life echoes till eternity!

Can’t believe I stayed glued to this story from start to finish. Bro, you’re good.

It’s just a shame that the evil ones got away with all their atrocities while others suffer in silence. On Sandra Ezekwesili, I’m not surprised she’s such a despicable human being, reason she’s still unmarried.

Huge credit to Oge Obi for her good fight and professionalism.

Really sorry for Peter, I hope he gets his life back on track.

My take away from this story is just to never allow the noise in the market distract me, cos I’ll be the biggest loser. Never to allow praise-singers mess with my head that I forget where I was coming from and where I needed to be.

Great read David!

Thank you for this piece…

David, the amount of effort you put into your work is just so inspiring. This was such a great and revealing read. The work environment of BBC West Africa truly stinks of unprofessionalism.