Beyond Conferences and Commitments: Decoding Africa’s Industrial Dilemma

In 2024, we witnessed African leaders jet-setting from one summit or conference to another, in some cases summoned by the host state, and as usual, responding with a ‘begging bowl approach’ in search of investments and (short-sighted) solutions to their respective economic challenges. Empirical evidence indicates that this jet-setting, for the most part, has had little or no substantial material benefit for the continent’s industrialisation prospects. Instead, we have seen the continued decline in Africa’s manufacturing output. The figures below from UNIDO’s Multilateral Industrial Policy Forum (MIPF) 2024 Conference paper, for example, highlight a widening industrialisation gap between Africa and the rest of the world.

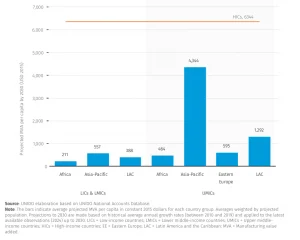

What is striking in this figure is that by 2030, low-income countries (LICs) and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) in Africa are projected to have an average manufacturing value added (MVA) per capita of just USD 211 compared to USD 6,344 in high-income countries (HICs). Moreover, the same projection shows that countries in East Asia, particularly China and, to some extent, India in the South, are markedly increasing their share of global industrial production, which is currently dominated by high-income countries (HICs). To put things in perspective, Africa accounts for only 2% of global MVA compared to Asia’s almost 45%.

Figure 1: The Growing Industrialisation Gap

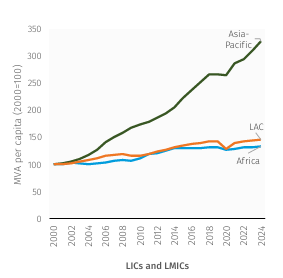

Figure 2: Industrial Dynamics in the Developing World

This indicates an emerging shift in the structural transformation of some countries in the developing world, while others, such as those in Africa, are witnessing only sluggish industrialisation. Over the years, I couldn’t help but observe the discourse on Africa’s industrialisation prospects and the continent’s interactions with China and India. We seem obsessed with where this growth comes from, with little or no interest in the policy-making structures and the embedded features that deliver this industrial growth. We need to reorient ourselves toward a discourse (both at the regional and national levels) on a new strategic industrial policy that must encompass three critical aspects, which I discuss below.

First, decentralised industrial policy-making would be crucial in enhancing our industrial prospects. I mean an embedded bottom-up policy-making approach whereby industrial policy frameworks are co-designed and implemented in strategic collaboration and coordination between national and sub-national governments, grassroots stakeholders, and the private sector. Let’s take India’s policy-making approach, for example. The country follows a federal structure where the central and sub-national governments play roles in developing industrial policy. Interestingly, states (i.e., sub-nationals) design specific policies that account for their local needs and conditions to attract industries, thereby creating competition among them. Such room for localised policy-making has allowed Indian states like Tamil Nadu and Gujarat to experience electronics production and manufacturing successes. With its centralised control system, even China allows its sub-national governments to develop and implement industrial policy frameworks that reflect their local realities, albeit aligned with national development objectives. Some commentators have described China in this aspect as having a quasi-federal structure. It is, however, encouraging to see that in certain African countries, such as Nigeria and South Africa, albeit with their limitations, some industrial policies are developed and implemented at sub-national levels. For example, Nigeria’s Lagos State Industrial Policy and South Africa’s Gauteng Township Economy Revitalisation Strategy (2014–2019). The former attracted the establishment of Africa’s largest privately owned refinery—the Dangote Refinery. Some commentators raise significant concerns that such a decentralised structure could lead to policy inconsistencies across sub-national entities and a lack of state capacity to implement them. Let me address the latter. These challenges are not insurmountable, and their difficulties should prompt innovative solutions rather than resignation. Also, it is important to remember that the journey to industrialisation is a discovery process that acknowledges the government’s lack of omniscience. With that in mind, as has been the case in the industrialisation processes of India and China, close collaboration with the private sector would help offset African governments’ weaknesses, especially if industrial policy is constructed to identify and address market constraints. For instance, despite its successes, India still faces many challenges to its state capacity but continues to develop institutions that drive growth. Dani Rodrik’s metaphorical description of State development is apt here: “State capacity is a muscle that develops as it is exercised.” Lastly, the national government, acting as a facilitating and coordinating force, could minimise the unintended consequences of policy inconsistencies across sub-national governments.

The second aspect is that we must orient our policy tools toward SMEs. Their importance in driving productivity and sustainable growth cannot be underestimated. Drawing on the experiences of India and China, a noticeable policy pattern is that, while encouraging FDIs (among other strategies that facilitate knowledge transfer between foreign and local firms), they focus on growing their own “little giants.” In contrast, African governments often show a chronic fixation on attracting FDIs rather than nurturing local enterprises. This is despite SMEs constituting over 70% of the private sector and contributing more than 50% to the continent’s GDP and 80% to employment.

Nevertheless, there has been a progressive shift in recent years. Take Nigeria’s Youth Enterprise With Innovation in Nigeria Programme (YouWIN!), for example, where MSMEs receive support packages based on their business plans and required activities. SMEs were selected through a business plan competition, allowing self-selection via an application process. Winners received customised business planning, finance, communication, operations, and mentoring support. McKenzie’s program evaluation positively impacted employment, profit, business survival, and increased entrepreneurial investments. Similarly, Kenya’s recently concluded Industry and Entrepreneurship Project (KIEP 250+) supports eligible SMEs through performance-based financing. While these initiatives are implemented nationally, their mechanisms could guide other African countries in developing their SME ecosystems. Additionally, unlike Nigeria and Kenya, other states could empower sub-national governments to lead in developing such mechanisms and must also know when to discontinue support if SMEs become uncompetitive.

The third aspect is that African governments must move away from applying uniform policy interventions across different sectors with the hope of achieving similar impacts—what development economists call horizontal policy intervention. India, China, and other developing countries strengthening their industrial bases have prioritised preferential/sectoral policies over horizontal approaches, which research has shown to be wasteful and largely ineffective. While much has been said about the drawbacks of such policies—including market distortions, rent-seeking, and fiscal burdens—solutions have been widely discussed by development economists, so I will not dwell on them here. However, one often overlooked factor influencing Africa’s policy-making direction is its colonial history, where a privileged few were favoured over the majority. Preferential policy interventions may seem socially undesirable, contradicting post-colonial ideals of inclusive socioeconomic development. Yet, the reality is that Africa cannot progress by attempting to cover all sectors simultaneously. There is an urgent need to focus on industries with strong growth potential. To be clear, I am not advocating that we forget our past but rather set aside historical sentiments for strategic economic reasoning. Without this shift, the continent risks remaining unprepared for the challenges ahead.

Author: Michael Asikabulu holds an MPhil in Development Studies from Cambridge University.

Read More:

- The Power of Community in Changing Mental Health Narratives

- DR Congo Cuts Ties with Rwanda as M23 Rebels Intensify Fighting and Advance into Goma

About The Author

Related Articles

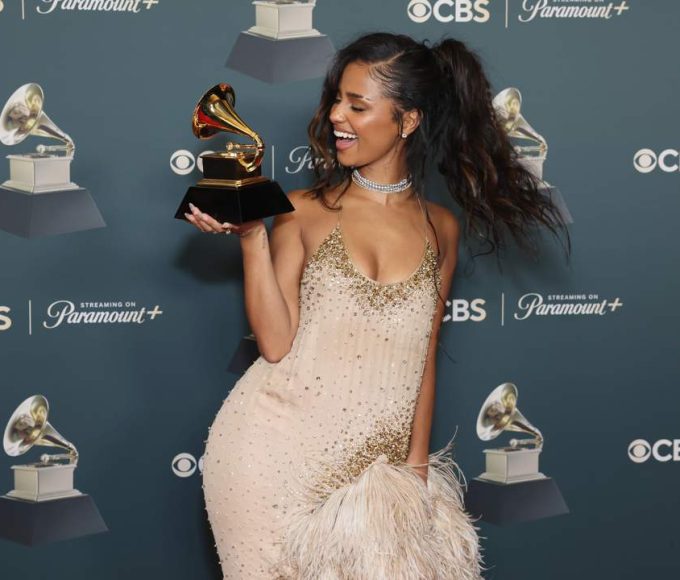

Tyla Wins Best African Music Performance at 2026 Grammys

South African singer Tyla has won the Best African Music Performance award...

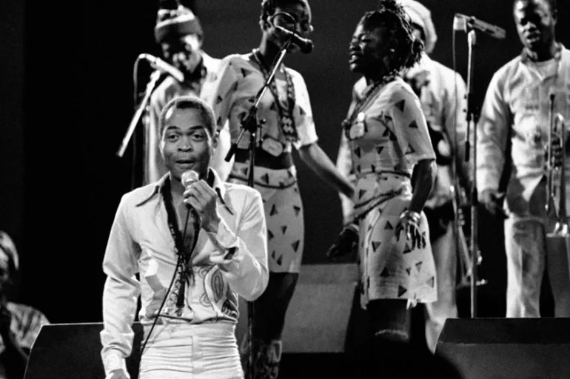

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Grammys Honour Fela Kuti With Historic Lifetime Achievement Award

Legendary Nigerian musician and Afrobeat pioneer Fela Anikulapo Kuti has become the...

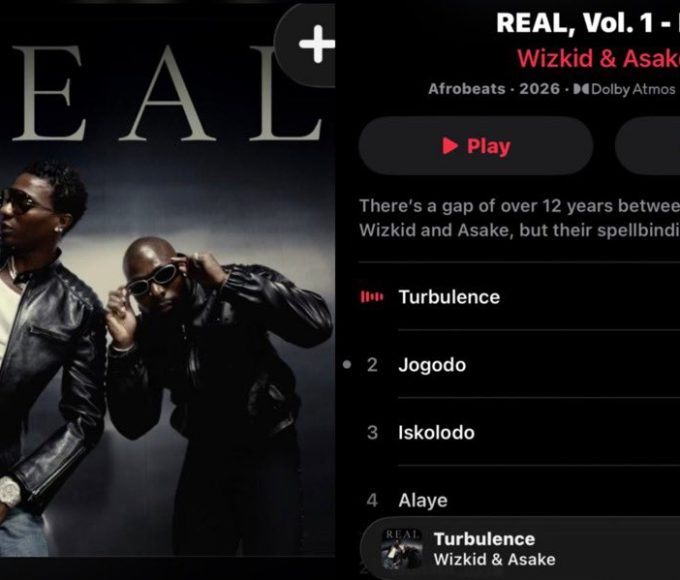

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Wizkid and Asake Join Forces on New Collaborative EP

Wizkid and Asake have released a collaborative EP, uniting two of Nigeria’s...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Tanzania Eyes Gold Sales as Aid Declines and Infrastructure Needs Grow

Tanzania is weighing plans to sell part of its gold reserves to...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026

Leave a comment