Ghana has ordered its most aggressive audit of the mining sector in a decade, deploying auditors, forensic accountants, and independent consultants to major mining sites across the country. The move represents a new push by the government to recover lost revenue, toughen regulation, and reassert control over its mineral wealth.

In a letter dated October 13, the Minerals Commission instructed mining companies, through the Ghana Chamber of Mines, to prepare for an audit that will commence on November 1, 2025, and continue through June 2026. Per the directive, mining firms must provide production logs for ten years, financial records for three years, along with accompanying permits, stockpiles, and shipping manifests by October 31, 2025. Following every site inspection, companies are to file company-specific reports within 30 days.

The audit will involve scrutinising production volumes, mineral flows, tax and royalty payments, and compliance with environmental laws. The event will take place in three stages, starting with Gold Fields’ Damang mine and Perseus in November, and concluding with Xtra-Gold’s Kibi unit in June 2026. Newmont, AngloGold Ashanti, Gold Fields, Perseus, Asante Gold, Zijin, and Xtra-Gold are among the big players that will all be covered.

Ghana last conducted a comprehensive audit of its mining industry in 2015, with the assistance of outside investigators; however, portions of that report were later contested by some companies.

The timing of the new audit is particularly critical. Gold prices have surged in 2025, jumping to over $ 4,380 a troy ounce in October, while governments across West Africa are under greater pressure than ever before to ensure mining companies pay their fair share to national coffers. In 2024, mining generated revenues of 17.7 billion Ghanaian cedis, buoyed by a 25% rise in gold output.

Economists have long argued that weak oversight, royalty disputes, and illicit financial flows have cost Ghana a substantial amount of revenue. Said Boakye, a researcher at the Institute for Fiscal Studies in Accra, emphasised the importance of regular scrutiny.

Special audits should be done every year, not periodically. It’s the only way to inform sound tax policy and unlock the sector’s true revenue potential, he said.

The audit is part of a larger government effort to reform Ghana’s mining governance, including pursuing shorter licence lengths, direct revenue-sharing with host communities, and reforming the mining law for the first time in nearly two decades.

Early this year, Ghana passed the GoldBod Act, establishing the Ghana Gold Board as the sole agency with the mandate to purchase, assay, sell, and export gold from licensed artisanal and small-scale miners. Beginning May 2025, foreigners have been prohibited from trading or purchasing artisanally mined gold; all transactions are now to be processed through the Gold Board. In July, President John Mahama inaugurated the GoldBod Task Force to combat illegal gold mining and smuggling operations.

These reforms have been designed to stem illicit gold flows, improve traceability, and increase value capture domestically while addressing the environmental harm caused by unregulated mining.

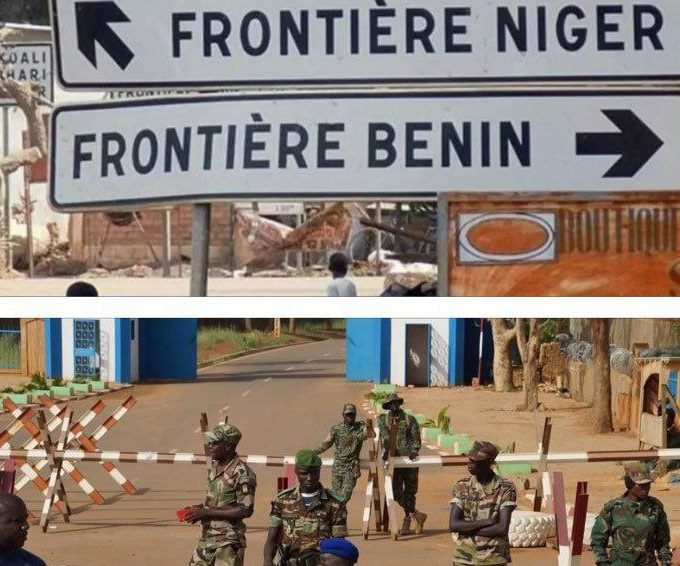

READ MORE: As Niger Celebrates New FIFA Mini-Pitches, Nigeria Faces Questions Over Misused Funds

The success of this audit and the subsequent reforms will, however, greatly depend on how they are implemented, as companies have historically resisted previous audits, disputing the findings and challenging the process. Forensic and physical audits at various remote sites will require well-resourced teams and strong logistical coordination. There are also concerns that if perceived as punitive or unevenly applied, it may deter future investment in Ghana’s mining sector.

Illegal gold smuggling remains one of the country’s most significant challenges. Reports estimate that Ghana lost as much as 11 billion dollars in five years due to unrecorded gold exports, especially to the United Arab Emirates.

If conducted effectively, the audit will help Ghana recover substantial revenues lost due to underreported mineral outputs or unpaid royalties. It could also bring about increased transparency, rebuild public confidence, and reset the relationship between the state and private mining firms.

For now, all eyes are on how the Minerals Commission will execute the process — and whether this audit marks a turning point in Ghana’s long struggle to ensure that its vast mineral wealth benefits its people appropriately.

Leave a comment