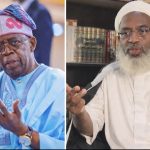

Tinubu Accused of Quietly Engaging and Negotiating With Terrorists as Hostages Are Freed Without a Single Arrest

In a dramatic turn after a week of mass kidnappings across Nigeria, security agencies announced the safe release of key abductees. Yet heavy questions linger over how the rescues were engineered, what they reveal about government strategy, and whether real reform is underway or simply crisis management.

On November 18, armed men stormed a church in the Eruku community of Kwara State, abducting 38 worshippers from a congregation of the Christ Apostolic Church. The move sparked fresh horror, following closely on the heels of a mass abduction at a girls’ boarding school in Kebbi and a major raid on a Catholic school in Niger State.

Five days later, on November 23, the Presidency announced that all 38 worshippers had been released. According to Bayo Onanuga, Special Adviser to the President on Information and Strategy, the release was secured not through a raid or heavy force but through what he described as a non-kinetic operation led by the DSS and the military. Onanuga said operatives used real-time tracking systems and direct contact with the bandits, delivering a firm ultimatum that convinced the kidnappers to free their captives.

Then, on November 25, every single one of the 24 schoolgirls abducted in Kebbi on November 17 was also reported freed. One girl had escaped on the day of the abduction, while the rest were rescued, though officials have chosen not to disclose the details of the rescue operation.

President Tinubu welcomed the development, calling the freed students accounted for and ordering heightened security in vulnerable forest zones across Kebbi, Kwara and Niger states. The government also pledged further support for security agencies working to free other abductees still in captivity.

But while the rescues brought relief, they reopened deep and systemic questions about insecurity, state response and the role of negotiation in the fight against terrorist violence.

Why the Rescues Raise Alarms, Not Celebration

For many Nigerians, the fact that terrorists could operate with impunity, abducting schoolchildren and worshippers across multiple states in a single week, is itself a damning indictment of how fragile the country’s security architecture has become. The successive kidnappings and raids suggest not isolated incidents but a coordinated wave of violence driven by fear, intimidation and ransom potential.

The non-kinetic rescue strategy used in Kwara, essentially a negotiation and pressure tactic rather than a military strike, raises an uneasy question: Does the state’s willingness to settle through communication amount to a form of bargaining with criminal networks? And if so, does that embolden the perpetrators to strike again, confident they can negotiate their way out without consequences?

Transparency also remains elusive. Despite the high-profile rescues, authorities have offered little detail about how security forces tracked the kidnappers or forced their compliance. No arrests have been publicly announced in connection with the Eruku or Kebbi abductions, deepening suspicions that negotiation and back-channel deals are replacing real justice and accountability.

Finally, the sequence of events under Tinubu’s watch is difficult to ignore. A major school abduction in Kebbi, a church attack in Kwara and a Catholic school raid in Niger State all occurred within days of each other. The repeated failures to prevent these attacks, especially in supposedly protected spaces like schools and places of worship, suggest structural weaknesses in intelligence gathering, preventive policing and community protection.

What This Means for Trust, Governance and Future Security

The government’s ability to secure the release of dozens of abductees may offer temporary relief, but it does little to counter the broader crisis. For ordinary Nigerians, the rescues reinforce a bitter truth: when terror strikes, safety comes not from strong institutions but from luck, negotiation or intervention at the highest levels.

For the state, the situation is a test of credibility. If the government cannot explain how it allowed so many large-scale abductions, or if it continues to rely on negotiation-based rescues without dismantling criminal networks, public trust may erode further.

In the short term, calls for enhanced protections, such as aerial surveillance, more boots on the ground in vulnerable zones, and improved intelligence sharing, may rise. But lasting peace will require more than reactive tactics. It will require systemic reforms, a stronger intelligence capacity, a genuine dismantling of criminal networks, transparent justice mechanisms, and a security strategy that protects citizens, not just retrieves them after they have been taken.

Until then, every rescued worshipper and every freed schoolgirl will remain a reminder of how deeply the crisis has scarred the nation, and how much work remains before Nigerians can once again feel safe in schools, churches and daily life.

Read: Military Takes Control in Guinea Bissau After Disputed Election in Fresh Coup d’État

About The Author

Related Articles

Asake Sets New Billboard Afrobeats Record as Chart Presence Grows

Asake has further cemented his place as one of Afrobeats’ most dominant...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Nigerians Lament PayPal’s Return as Old Wounds Resurface

PayPal’s reentry into Nigeria through a partnership with local fintech company Paga...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Tanzania Eyes Gold Sales as Aid Declines and Infrastructure Needs Grow

Tanzania is weighing plans to sell part of its gold reserves to...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Mali Tightens Grip on Explosives Supply With New Majority Stake

The Malian government has taken majority ownership of a civil explosives manufacturing...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026

Leave a comment