‘The Eyes of Ghana’ Premieres at TIFF and Revives Kwame Nkrumah’s Dream of Cinema and Liberation

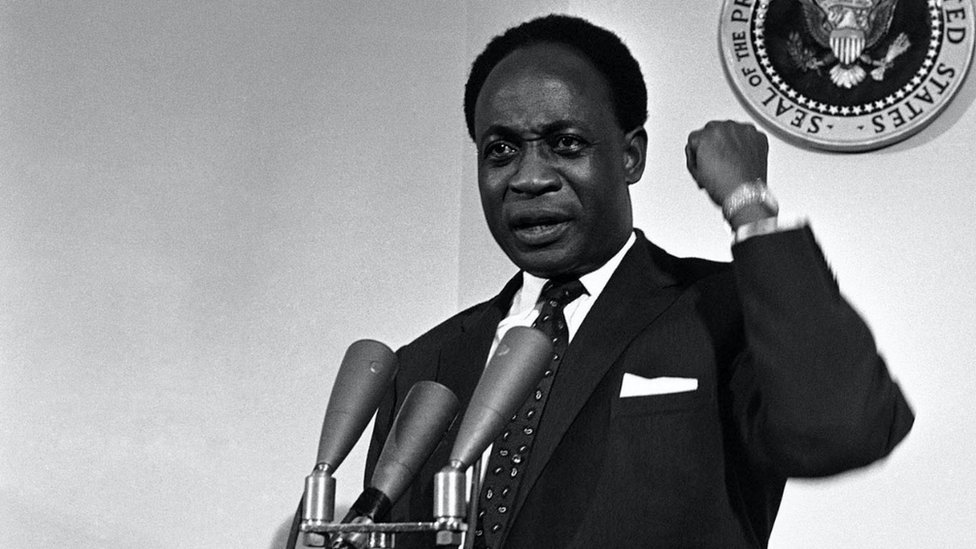

At a time when stories about African identity so often get filtered through the eyes of others, ‘The Eyes of Ghana’ arrives at TIFF 2025 as not just a documentary, but as a reclaiming. Produced and executive produced by Barack and Michelle Obama and directed by Ben Proudfoot, the film brings Kwame Nkrumah’s vision into a cutting focus: Ghana’s first Prime Minister and one of the principal designers of post-colonial African independence, and his enduring belief that film could cure and liberate.

The film is about Chris Tsui Hesse, aged 93 now, who was Nkrumah’s personal cinematographer and film chronicler for Ghana’s early years of independence. It is from the eyes (both literal and metaphorical) of Hesse that we catch a glimpse of a youthful independent Ghana: a country resolved that it had to tell its own stories in an attempt to reverse the colonial stereotypes. Hesse chronicled not only political events and speeches, but talks with world leaders, journeys across newly independent Africa, and the texture of daily life in a government teeming with promise.

One of the unifying threads that runs throughout ‘The Eyes of Ghana’ is urgency. Nkrumah did not simply see film as a work of art, but as a weapon: an antidote to caricature colonialism had made of Africa. He drew inspiration from his own experience as an international student in the U.S., where he observed the impact of film on public opinion, identity, and community, and believed Ghana could establish its own film industry (the Ghana Film Industry Corporation, GFIC) to portray its people with dignity and complexity.

But this reclaim had its glitches. Some of Hesse’s film reels were thought to be destroyed or lost in the aftermath of political unrest. The Eyes of Ghana reconstitutes what remains, afraid footage, restored screenings, public cinema theatres like the Rex Theatre in Accra, and pairs them with contemporary voices: Anita Afonu, filmmaker and producer, and “Mr. Farmer-driven. Addo, the activist projectionist, rescues outdoor theatre exhibitions. These figures bridge past and present, reminding viewers this isn’t nostalgia, but a continuing struggle over control of image and memory.

Visually, the film explores the tension between grainy historical footage and the texture of modern memory. We glimpse Hesse’s face, lined but not blurred, as we remember walking with Nkrumah, filming backstage, watching state visits, and capturing moments of political theatre and mass desire all at once. The restored cinema found its voice again; the footage long held in vaults is now screened once more. The film frames these moments not merely as history, but as identity claims and self-representations of today.

Significantly, the film does not present Nkrumah as flawless. There is room for doubt. The film prompts one to question propaganda, the use of images to promote political power, and whether all government-commissioned films are altruistically motivated. Hesse himself sometimes stops short of passing a moral judgment, leaving audiences to view and decide for themselves. This discretion renders it more effective: a history lesson, undoubtedly, but one which invites thought rather than hagiography.

For far too many Ghanaian and diasporan individuals, ‘The Eyes of Ghana’ comes at the right time. There is renewed interest in Nkrumah, not just as myth, but as inspiration. Younger generations hungry for roots, authenticity, and auctoritas of storytelling are discovering value in these reappropriated images. Anita Afonu describes finding Hesse’s writing as an eye-opening experience: suddenly, there are possibilities of how one can write stories that feel like home, that uncover joy, struggle, hope, and all the in-betweens.

With ‘The Eyes of Ghana,’ cinema is restored not as art alone, but as archive; not as spectacle, but as self-portrait. It reminds us that to Africa, the camera has never been a neutral eye, and its handlers are accountable. As Hesse’s documentary images flash before us on screens, the past is illuminated, and with it, a future that refuses to be written from outside in.

Read More:

- Kenya’s Ruto Proposes Mediating Nile Dam Dispute, Seeks to Purchase Ethiopia’s Power

- Nigerian Government Pushes “IMF-Debt-Free” Media Narrative As Nigeria Becomes Africa’s Largest World Bank Debtor

About The Author

Related Articles

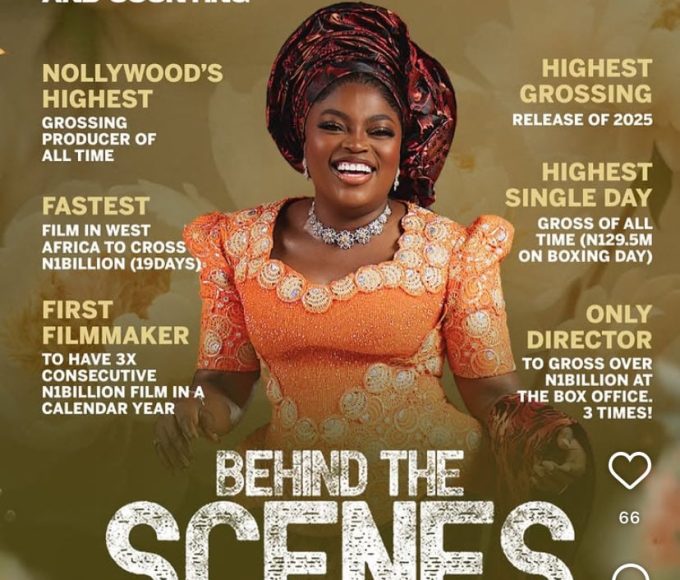

Funke Akindele Extends Box Office Streak as New Film Hits ₦1bn

Nollywood actress and filmmaker Funke Akindele has set a new box office...

ByWest Africa WeeklyDecember 31, 2025Wizkid, Seyi Vibez, and Asake Dominate Spotify’s 2025 Wrapped in Nigeria

Spotify has released its 2025 Wrapped data, and the results show another...

ByWest Africa WeeklyDecember 4, 2025Lagos Welcomes XVI Edition of S16 Film Festival Featuring Shorts, Features, and Panels

The 2025 edition of the S16 Film Festival officially opened in Lagos...

ByWest Africa WeeklyDecember 3, 2025Ghana Sets Up GH₵20m Creative Arts Fund as Nigeria’s Sector Still Lacks Support

Ghana’s 2026 national budget includes a bold new investment in its creative...

ByIkenna ChurchillNovember 17, 2025

Leave a comment