French Media Giant Canal+ Buys Out MultiChoice in $3B Deal

French media company Canal+ has officially acquired full ownership of MultiChoice, Africa’s biggest pay-TV provider, in a $3 billion deal that could reshape the continent’s media industry. The transaction, which was approved by South African authorities, gives Canal+ complete control of DStv, GOtv, and other prominent African content brands.

This landmark move means Canal+ now reaches over 14.5 million subscribers across 50 African countries, with the deal expected to be fully closed by October 8, 2025. The company plans to invest R26 billion (approximately $1.4 billion) over the next three years to boost local content, safeguard jobs, and maintain MultiChoice’s South African roots.

“This is a strategic milestone for our company,” said Canal+ Chairman and CEO Maxime Saada. “We aim to build a unified media platform that blends Canal+’s French-language programming with MultiChoice’s English and Portuguese content, while boosting local production.”

Canal+ began purchasing shares in MultiChoice in 2020 and gradually accumulated a 45 per cent stake. This final buyout now positions the company to compete with global streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video, particularly through African platforms such as Showmax, Africa Magic, M-Net, and SuperSport.

For many African creatives and viewers, this deal could mean more opportunities, more visibility, and more African stories being told to the world.

Read More:

- U.S.-Funded PR Network Secretly Targets Nigerian GMO Critics While Enlisting Doctors and Journalists to Shape Public Opinion

- Google Unveils $37m AI Push Across Africa, Targeting Agriculture, Health, Education in Ghana, Nigeria and Others

About The Author

%s Comment

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related Articles

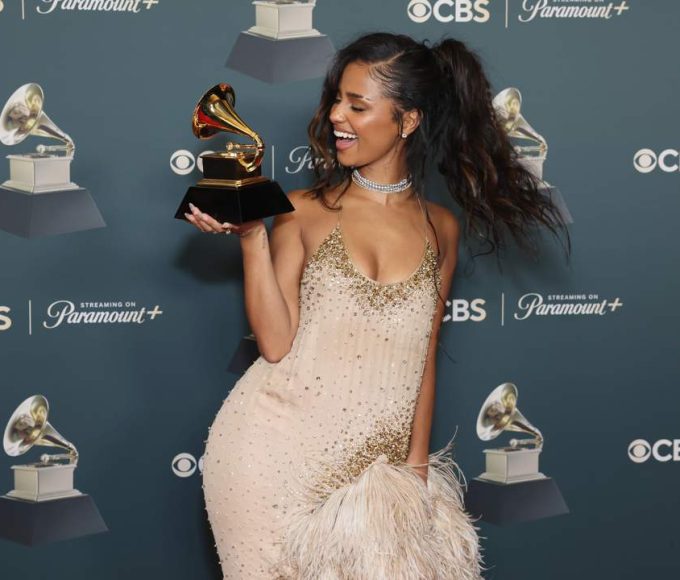

Tyla Wins Best African Music Performance at 2026 Grammys

South African singer Tyla has won the Best African Music Performance award...

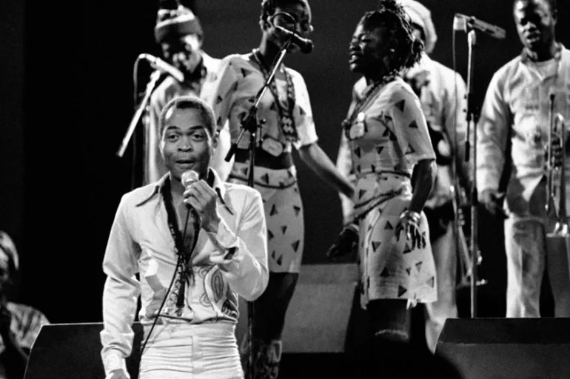

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Grammys Honour Fela Kuti With Historic Lifetime Achievement Award

Legendary Nigerian musician and Afrobeat pioneer Fela Anikulapo Kuti has become the...

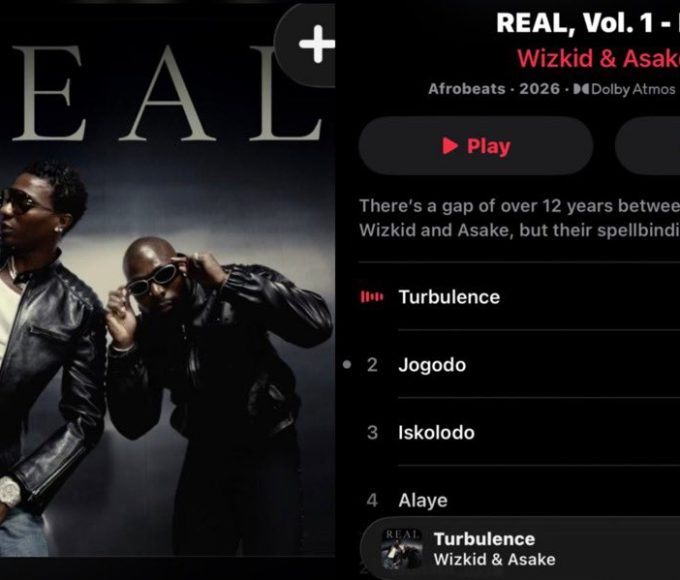

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Wizkid and Asake Join Forces on New Collaborative EP

Wizkid and Asake have released a collaborative EP, uniting two of Nigeria’s...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Toyin Abraham Joins Funke Akindele as Nollywood Billionaire Filmmaker with Oversabi Aunty

Veteran actress, producer, and now director Toyin Abraham Ajeyemi has reached a...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 28, 2026

This is not just a business deal. It is a strategic soft power acquisition, especially as African nations like Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso push back against French military and political involvement. If France can no longer dominate Africa with troops or diplomacy, it will do so with media.

The implications are immense:

• Editorial decisions about African stories may now be made in Paris, not Lagos, Nairobi or Johannesburg.

• African content creators may be forced to conform to European corporate policies and values.

• Narratives critical of France, the EU, or Western hegemony may be subtly filtered, deprioritized, or outright censored.

The West may no longer wear the badge of colonial authority, but its media machines now serve a similar function controlling what stories are told, who tells them, and how the world sees Africa.

If Africans do not control their own narratives, someone else will. And as we’ve seen, they already are.