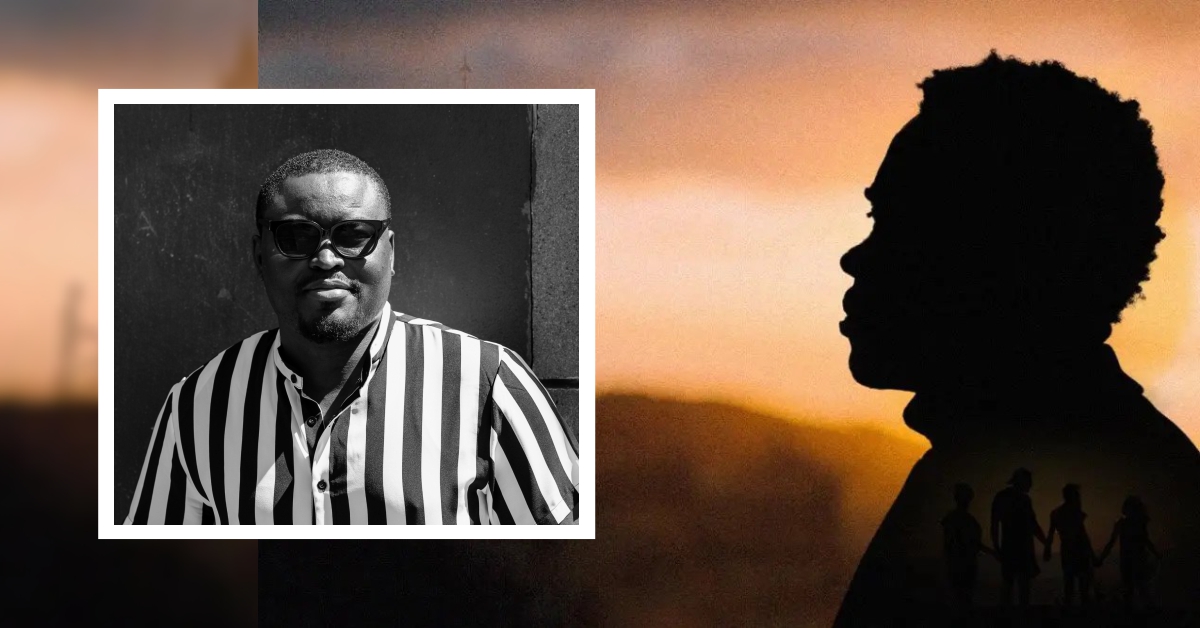

Babatunde Apalowo’s Next Nollywood Film, Londoner, Is Personal, but Its Questions Are Collective

Babatunde Apalowo has always been drawn to stories that feel intimate. His debut, All the Colours of the World Are Between Black and White, was a quiet revelation, a tender portrait of love, longing, and identity in Lagos that went on to win the Teddy Award at the 2023 Berlinale. His next film, Londoner, is shaping up to be just as personal, though in a different register. On the surface, it is a migration story, but beneath it lives a deeper meditation on family, masculinity, forgiveness, and the shifting idea of home.

When I first reached out to him, I wasn’t sure he would reply. He has admitted before that he dislikes most interviews, dismissing many as repetitive or shallow. Still, I wrote to him, first by email, then by Instagram DM, and waited. By the time we finally spoke on a Sunday afternoon, he explained why he had held back.

I wanted this to be at a time when I wasn’t rushing, he said. So I could prepare, sit with my morning coffee, and really give you something honest.

It no longer felt like an ordinary interview but something else, a conversation that reached beyond cinema into memory, family, and the messiness of living between worlds. Apalowo’s voice was calm, deliberate, as though every word carried the weight of both confession and restraint. He is, after all, a filmmaker who understands silence as much as dialogue, the unsaid as much as the spoken.

Apalowo’s reputation was already sealed with All the Colours of the World Are Between Black and White, his debut feature that premiered at the Berlinale in 2023 and went on to win the Teddy Award. That film, tender and understated, told a story of forbidden love and unspoken yearning in Lagos. It announced him as a director willing to risk quietness in an industry that often leans toward spectacle. With Londoner, his next film, he is moving into even more personal territory. The project is still in development, but he speaks about it with the gravity of something already living inside him. That private conviction has already found public recognition: earlier this year, Londoner won the Red Sea Film Fund Award for Best Fiction Feature at the Durban FilmMart, where it was praised for its intimate take on migration and identity. For Apalowo, the award was less about prestige than about affirmation, that the story deserved to exist even before a single frame was shot.

I think Londoner is less an immigrant story, he told me. It’s more of a family story. A character study of humanity and relationships. He paused, as though weighing whether to let the following sentence out. It’s about the contradictions we all carry. The things we run away from, the things we still long for. The way leaving doesn’t always mean freedom. The way returning doesn’t always mean home.

At its core, Londoner follows a Nigerian man who leaves for the UK and eventually decides to return. But the film refuses the neat arc of hardship abroad followed by triumphant homecoming. Apalowo is interested in the in-between, in the confusion of return, in the silences that open between family members when roles and expectations shift. “The character doesn’t go back because he must,” he said. “He goes back because he chooses to. And that choice is where the tension lives.”

That tension mirrors broader cultural dynamics Apalowo himself has observed while moving between Lagos and London. In Nigeria, respect for a father or a man of a certain age is often automatic. In England, it must be earned, negotiated, and tested. It was a humbling recalibration, and one he could not ignore. “In Nigeria, I never questioned my authority in the family. In the UK, I suddenly discovered that love and respect have to be negotiated. That vulnerability is not weakness but necessity.”

Vulnerability is a word that keeps circling back in his speech.

Life would be very nice if all of us could go on a boat with each other and cry on our shoulders, he said with a half-smile. But life is not like that. Vulnerability is often seen as danger, especially for African men. But for me, it’s not a weakness. It’s part of being human.

Londoner becomes, in that sense, not just a story of migration but of masculinity itself, how fathers, husbands, and sons learn (or fail) to inhabit softness.

Our talk drifted to forgiveness, a theme that shapes not only his work but also the cultural lens through which he approaches it. “I had to forgive my father,” he admitted. “Even in places where forgiveness felt impossible. And more importantly, I had to forgive myself.” He described forgiveness not as resolution but as ongoing work, a negotiation between memory and desire. In his films, characters often stumble through that same negotiation, carrying wounds they cannot heal. “Silence,” he said, “is never empty. It holds its own power.”

When I asked him what home means, he surprised me. “Home right now to me is cinema,” he said without hesitation. Then he turned the question back on me.

For me, home is watching my aunt bake, my mother cook, my sister read, my cousins chat, each of them doing what they love, not what work demands. That is what home is to me. Not bricks or geography, but the freedom to do what you love, together, in community.

That sense of home, I told him, extends to creative kinship too. If I am around someone who is creatively minded and understands the craft, even if they are not doing exactly what I do, I feel at home. Because of that resonance, that shared pursuit of what you love, that is home too.

This idea of home as memory, as continuity, was sharpened by his reflections on Nigeria itself. I told him about a post I had seen, where someone renovated an old house in a way that stripped it of creativity and character, replacing history with empty modernity. From there, he spoke with sadness about how we demolish buildings instead of preserving them, how we lack architectural memory.

In London, you walk past churches built 200 years ago and still in use. In Nigeria, we replace everything. We forget. Our culture has stopped evolving.

For him, cinema becomes one way of resisting that erasure, of insisting that culture must be preserved, documented, and allowed to grow.

Here, Apalowo becomes not just a filmmaker but a cultural critic. He worries that Nollywood, in its pursuit of global recognition, too often flattens itself into spectacle or nostalgic epic. He wants something more alive. “Our culture is not static. English has undergone significant changes over the past 500 years. Why shouldn’t Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa evolve in cinema too?” He revealed that his next project after Londoner will be entirely in Yoruba, not just the dialogue but even the credits. “It’s about reclaiming our frameworks of thought. Culture isn’t just costumes and sets. It’s how we think, how we tell stories, how we structure narrative logic.” In his vision, Yoruba philosophy itself could shape cinematic form, circular narratives, silences, and repetitions. “It’s not about putting culture in the frame,” he said. “It’s about letting culture be the intellectual engine of the film.”

Listening to him, it became clear that Londoner is not just another migration drama. It is also a manifesto of sorts, an argument for vulnerability, forgiveness, and cultural continuity. It is an attempt to write against absence, the absence of memory, the absence of space for softness, the absence of personal stories in mainstream Nollywood. “I’m making it for myself,” he told me. “And I hope when people watch my film, they see themselves reflected as Nigerians in a way they haven’t seen before. And they feel respected, as Nigerians and as human beings.”

As we spoke, time slipped away. It felt less like an interview than a shared reckoning. He asked me about my own story, and I told him about my mother, a journalist, and my father’s piles of newspapers at home. He nodded, as though to say, yes, this too is part of the exact search. When our call ended, I sat still for a long while, struck by how rare this was. He doesn’t give many interviews. He guards his story carefully. And yet, on this Sunday afternoon, with his coffee cooling on the table, he let me into the contradictions, silences, and hopes that fuel his art.

When Londoner eventually comes to life, it will carry the weight of these conversations. It is still in development, but in Apalowo’s words and vision, the film already exists as a mirror, one that reflects the contradictions of leaving, returning, and belonging. What struck me most was how deeply personal it is, and yet how easily it expands to all of us who live in that in-between space.

Apalowo isn’t promising answers. He is, instead, holding space for questions: What does it mean to forgive? To soften? To carry memory when the world erases it? These are not just questions for a character on screen. They are questions for Nigeria, for Nollywood, for all of us.

Read More:

- Nigeria’s National Grid Collapses Again, Plunging Cities Into Darkness

- Malian Army Destroys Terrorist Base in Kayes Region

About The Author

Related Articles

Tyla Wins Best African Music Performance at 2026 Grammys

South African singer Tyla has won the Best African Music Performance award...

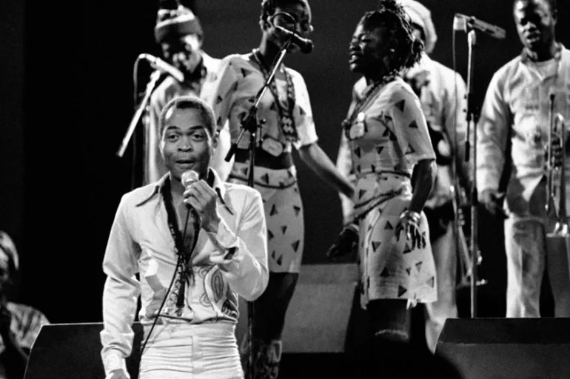

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Grammys Honour Fela Kuti With Historic Lifetime Achievement Award

Legendary Nigerian musician and Afrobeat pioneer Fela Anikulapo Kuti has become the...

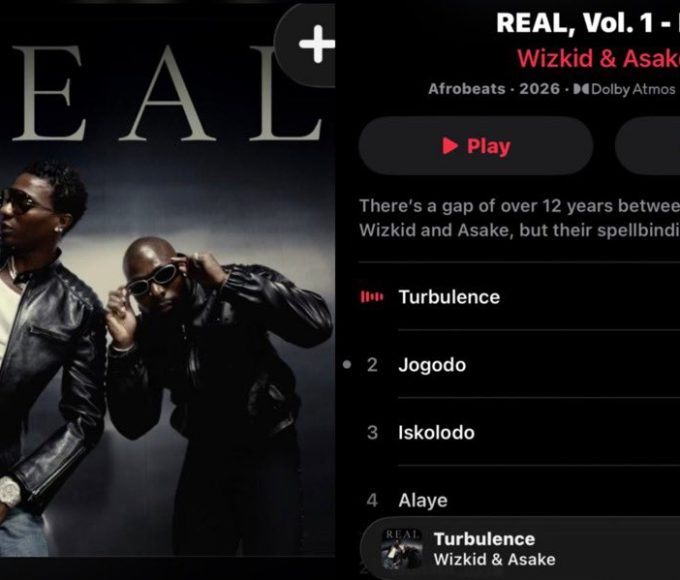

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 2, 2026Wizkid and Asake Join Forces on New Collaborative EP

Wizkid and Asake have released a collaborative EP, uniting two of Nigeria’s...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 29, 2026Toyin Abraham Joins Funke Akindele as Nollywood Billionaire Filmmaker with Oversabi Aunty

Veteran actress, producer, and now director Toyin Abraham Ajeyemi has reached a...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 28, 2026

Leave a comment