Africa’s Online Propaganda Machine Where Politicians And Foreign Powers Use Paid Influencers To Rig Elections And Rewrite Reality

Across Africa and in Western political strategies, there is a growing trend of political actors abandoning traditional media in favour of secretly employing social media influencers to disseminate propaganda and influence elections. This shift signals a new era of digital warfare in which the lines between authentic grassroots support and paid manipulation are increasingly blurred.

Kenya’s 2022 presidential election serves as an example of the commodification of digital influence. Online engagement was transformed into a transactional marketplace, with some influencers reportedly earning between $1,000 and $2,000 per tweet. In a country with over 11.8 million social media users, influencers played a central role in promoting campaign narratives and generating traction through hashtags and viral content.

Key tactics observed during Kenya’s election included coordinated fake engagement using bots, with William Ruto’s campaigns relying on digital automation to amplify their messages. Influencers also challenged traditional media institutions and judicial authorities, weakening key pillars of democracy. Online strategies such as follow trains, hashjacking, and astroturfing were used to manipulate visibility on platforms.

In contrast, conspiratorial narratives, such as the “deep state” framing, were deployed to distance candidates from past administrations and discredit democratic institutions. One such effort, the Hustler Nation Intelligence Bureau, actively encouraged digital vigilantism by urging followers to name and shame perceived political enemies.

Interestingly, many of the influencers involved in these operations were typically associated with consumer products or fashion but temporarily pivoted to political content, leveraging their existing audiences for political ends. Groups of influencers often collaborated, even hiring university students to disseminate narratives on a large scale.

Research from the Institute for Security Studies, based on over eight million Facebook and Twitter posts, concluded that while the disinformation was primarily homegrown, Kenya’s digital influence model could easily be exported to other African nations or exploited by foreign actors and criminal networks. With the rise of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT, the velocity and complexity of these operations are expected to increase, contributing to what experts are calling a global arms race in AI-enhanced influence campaigning.

In Nigeria’s 2023 general elections, political parties also paid influencers, often in secret, to circulate disinformation. A BBC investigation revealed that influencers were compensated not only with large sums of money, up to ₦20 million (approximately $45,000), but also with gifts, government contracts, and even political appointments. Political “situation rooms” monitored the performance of false narratives being pushed on social media, as if tracking a digital military campaign.

Influencers admitted to posting completely fabricated stories, which they often distributed through networks of micro-influencers. Campaigns frequently exploited Nigeria’s sensitive religious, ethnic, and regional divisions. False narratives linked candidates to groups like Boko Haram or separatist movements such as IPOB.

Politicians instructed influencers to provoke emotional reactions using unrelated but powerful imagery, designed to maximise shares and engagement. Some influencers were given general messaging prompts; others received pre-written tweets to post at scheduled intervals. Payments were typically made in cash, leaving no traceable paper trail.

While hiring influencers is not illegal in Nigeria, spreading falsehoods is a violation of national law and social media policies. But, platforms like X have been criticised for failing to enforce rules in African contexts, especially after significant staff cuts. The result is a compromised public information space in which manipulation masquerades as popular opinion.

Investigative journalist David Hundeyin further alleged that the Nigerian government, with backing from the IMF, recently organised a trip for influencers to Ghana to produce misleading price comparisons. The goal was reportedly to normalise upcoming tax increases in Nigeria by presenting Ghana’s 15 per cent VAT as a standard, conveniently omitting differences in income levels.

In Namibia’s 2024 election, digital campaigning largely replaced the traditional methods. Social media has become the epicentre of political warfare, with campaigns fueled by insults, misinformation, and paid propaganda. Influencers are now key agents of electoral strategy, promoting party messages across platforms without always disclosing sponsorship. Both the ruling Swapo party and the opposition IPC have been accused of using paid influencers to push partisan narratives, further blurring the boundary between authentic discourse and manipulation.

This phenomenon is not unique to Africa. The Israeli government, for example, has funded trips for right-wing American influencers, particularly supporters of Donald Trump’s MAGA and America First movements, to tour Israel and shape narratives among young American conservatives. The foreign ministry aims to bring 550 such delegations by year’s end, believing influencer endorsements are more persuasive than official government messaging. One such strategy involved taking influencers to witness the distribution of humanitarian aid in Gaza, aiming to reframe international perceptions. These young influencers, many with millions of followers, are now a critical vector in Israel’s battle for global public opinion.

South Africa, too, appears increasingly vulnerable to digital manipulation. Political parties and interest groups have been employing networks of nano-influencers, typically followed by only a few thousand people, to create the illusion of widespread grassroots support. These influencers are reportedly paid between R50 and R250 per post and are rarely transparent about their affiliations.

Their goal is not debate, but deception, and to flood the information space with orchestrated enthusiasm, drowning out dissent. Yet there are currently no clear guidelines from South Africa’s Electoral Commission regarding paid political content by influencers. Without urgent action, including media literacy campaigns, political accountability, platform transparency, and regulatory reform, the country’s 2026 local elections could be dominated by social media disinformation disguised as public sentiment.

Despite these concerning trends, there are examples of social media being used ethically and strategically by ordinary citizens. In rural Zimbabwe, for instance, a group of older women have organised on WhatsApp to counter election intimidation and biased state media. These grandmothers share updates and information from the opposition Citizens Coalition for Change, helping communities engage with politics from the safety of their homes. This grassroots resistance demonstrates that, while digital tools are vulnerable to abuse, they also provide powerful avenues for civic participation and democratic resilience.

Across both African and Western political arenas, the weaponisation of influencers to bypass traditional media and manipulate public opinion represents a fundamental threat to democratic integrity. What began as a tool for brand marketing has evolved into a sophisticated political instrument, one that can distort reality, inflame divisions, and erode trust in institutions. As global elections approach in 2026 and beyond, the battle for truth will be increasingly fought not in newsrooms or public squares, but in the algorithmic shadows of our digital lives.

Read More:

- Tribalism Is Not African: Africa’s Wounds Were Carved In Western Boardrooms And Remain A Colonial Tool Still In Use

- Despite Empty Booth Setback at TICAD9, Tinubu Regime Falsely Claims Japan Approved ‘Special Visa’ for Nigerians in Kisarazu

About The Author

Related Articles

Surviving Poverty Through Pollution: A Day in the Life of Adamawa Bola Boys

Before leaving Lagos, I was sure that I had left behind memories like...

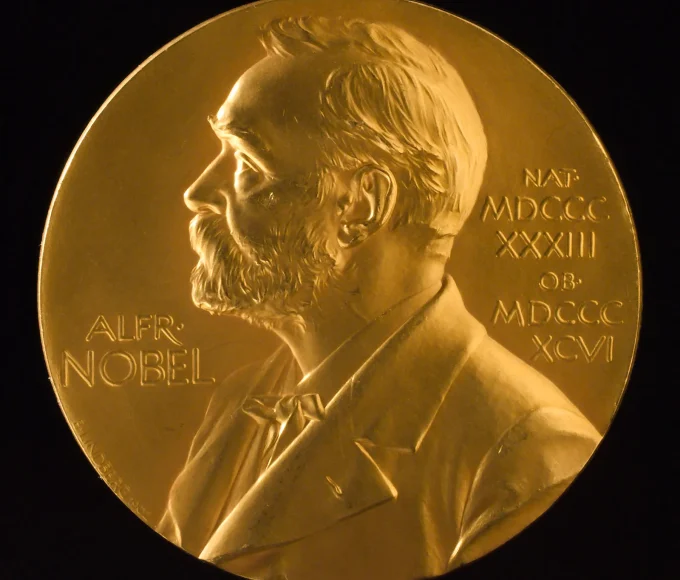

ByBankole Taiwo JamesNovember 20, 2025The Nobel Peace Prize: A Weapon of Western Hegemony

From Dynamite to Diplomacy, the Birth of a Paradox Alfred Nobel, the...

ByAbdirahman Mohamed AhmedOctober 13, 2025Everything You Know About Africa Might Be a Lie: The Scripted Continent and How the West Engineered Its Story Before It Happened

What if the negative perceptions surrounding Africa are not simply organic but...

ByWest Africa WeeklySeptember 20, 2025Ethiopia: Israel’s Twin In Africa Expansionism, Proxy Wars, And The Assault On Sovereignty

For generations, Ethiopia has functioned as the “Israel of Africa.” It is...

ByAbdirahman Mohamed AhmedSeptember 18, 2025

Leave a comment