On December 29, 2023, South Africa filed an 84-page suit based on the 1948 United Nations Genocide Convention at the International Court of Justice against Israel, alleging that the latter is committing genocide against the people of Palestine in Gaza. Both countries were signatories to the convention and were, therefore, bound by it.

The suit lists the “killing of Palestinians in Gaza in large numbers, especially children; the destruction of their homes; their expulsion and displacement; and a blockade on food, water and medical assistance to the strip as acts of genocide. It also includes the destruction of essential health services crucial for the survival of pregnant women and babies as further crimes of genocide against Israel.”

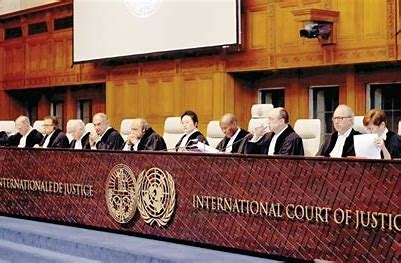

The preliminary hearing started on Thursday, January 11, 2024, with South Africa asking the ICJ to urgently order the Israeli military out of Gaza and for Israel to stop the “indiscriminate bombing of civilians”. The ICJ allows this sort of request as an interim order to protect against further violations that form the basis of the suit brought before it.

South Africa argues that provisional (interim) measures are necessary “to protect against further, severe and irreparable harm to the rights of the Palestinian people under the Genocide Convention, which continue to be violated with impunity”.

If approved, the ICJ could issue an order in weeks, similar to the order granted in Ukraine v Russia. The ICJ issued an emergency order against Moscow’s invasion in less than three weeks. The court, on March 16, 2022, ordered Russia to “immediately suspend the military operations”.

The ICJ is comprised of 15 judges appointed for nine-year terms. Elections are conducted separately and simultaneously at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) and the UN Security Council. No two judges must come from one country, although all countries are eligible to participate. The current bench includes judges from around the world, including Australia, India, Jamaica, and Uganda.

At the moment, the President of the ICJ is Joan E Donoghue of the United States. He is deputized by Vice President Kirill Gevorgian of Russia. Their terms in the ICJ expire in February.

Israel and South Africa were allowed to appoint one “ad hoc” judge each to join the bench as parties in the suit since neither is represented currently. Aharon Barak, a former Supreme Court chief justice and Holocaust survivor, was chosen by Israel. Dikgang Moseneke, a former deputy chief justice, leads South Africa’s team.

Israel selected British lawyer Malcolm Shaw to be on its legal team. South Africa’s team is led by John Dugard, a professor of international law.

Although the provisional hearing will be over in a few weeks, the main case, which will determine if Israel is indeed guilty of genocide, will take much longer. The court will give both parties adequate time to build their cases and submit robust arguments. This would involve multiple hearings. Then, the judges would vote, and a final decision would be announced.

ICJ judgments are legally binding and cannot be appealed, but they cannot be enforced by the court. If Israel does not comply, South Africa can approach the UN Security Council for enforcement. The US has veto power as a permanent member and can shield Israel from punishment, as it has done multiple times in the past. The US has vetoed nearly all UNSC draft resolutions related to the Israel-Palestine conflict since 1945).

South Africa compared the Israeli occupation to the apartheid. Veterans of the apartheid struggle and a large proportion of the politicians (ruling party and opposition) have expressed their support of the case before the ICJ.

However, many suspect South Africa’s true intentions for pursuing the case may not be altruistic.

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s party has lost a lot of support from South Africans due to corruption within its ranks and a failure to address electricity shortages, poverty, and the rising cost of living.

About The Author

Related Articles

Malian Army Says Dozens of Militants Killed in Airstrikes in Segou Region

Mali’s armed forces say they have killed about twenty suspected militants during...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 19, 2026Nigeria Approves 33 New Universities While Education Quality and Jobs Remain in Crisis

Nigeria has approved 33 new universities, bringing the total number of sanctioned...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 19, 2026Gabon Suspends Social Media “Until Further Notice” Amid Rising Unrest

Gabon’s media regulator has announced the suspension of social media platforms nationwide,...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 18, 2026Côte d’Ivoire Feeds the World’s Chocolate Industry, But When Prices Shift, Cocoa Farmers Are Left With Rotting Harvests and No Income

Côte d’Ivoire produces nearly half of the world’s cocoa, a crop that...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 18, 2026