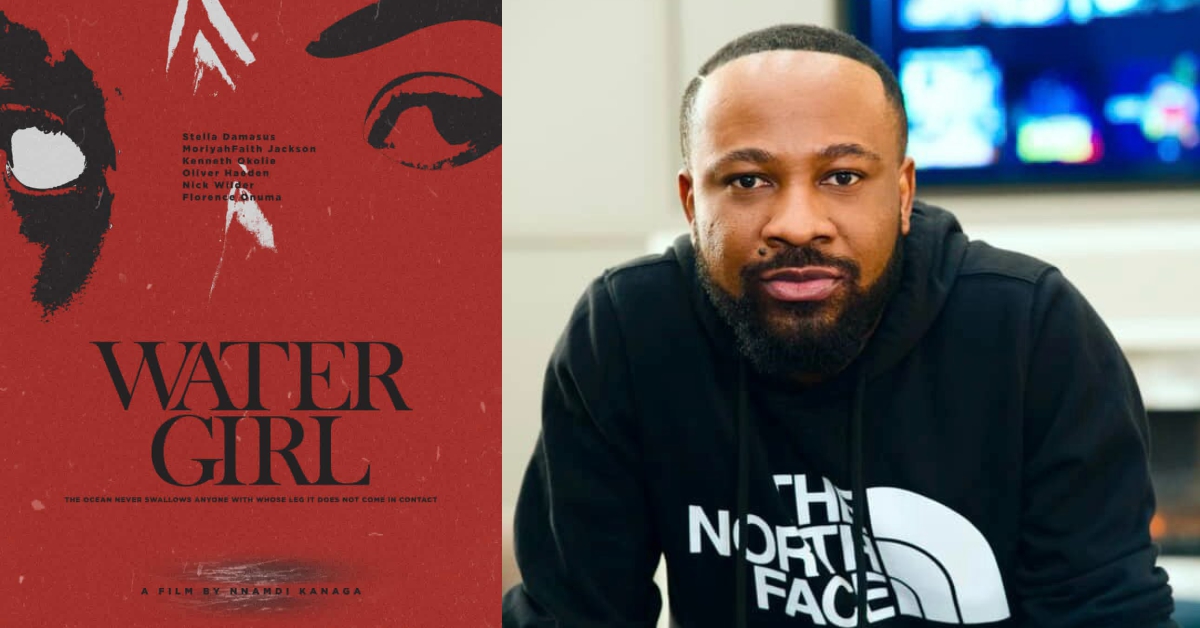

Nnamdi Kanaga’s “Water Girl” and the New Wave of Mythmaking in Nigerian Cinema

The crackle of a Montana winter seems worlds away from the humid whispers of Igbo folklore. Yet, in a Bozeman editing suite, filmmaker Nnamdi Kanaga watches a river spirit ripple across his screen; a creature born of ancestral memory and diasporic imagination. “Water Girl,” his genre-bending third directorial feature as an indie filmmaker, isn’t just a film. “It’s my spiritual awakening,” he tells West Africa Weekly, voice thick with conviction. “A sign I’m where I belong.”

For Kanaga, this awakening mirrors a seismic shift in Nigerian cinema. Directors like CJ Obasi (Mami Wata) and Dika Ofoma (Kachifo), along with a bold new vanguard, are plunging into mythology’s depths, transforming age-old spirits into vessels for contemporary storytelling. No longer confined to the moralistic horror tropes of 1990s Nollywood, creatures like the Ọgbánje (a vengeful spirit-child) and the water goddess Mami Wata now dissect colonialism, environmental rage, and cultural displacement.

Kanaga’s journey began with childhood viewings of classics like Unsympathy and Egg of Life (early 2000s), where spirits were depicted as simplistic villains. “Those films sparked curiosity, he recalls. But I craved depth. Why do these entities exist?” What human truths do they mirror?”

This hunger led to “Water Girl’s” five-year gestation. His reimagining of the Ọgbánje, a water spirit embodying ecological grief, became the film’s core. ‘She’s not evil; she’s a consequence,’ Kanaga insists.” Kanaga emphasises. To strike a balance between creative liberty and cultural fidelity, he conducted extensive research.

Some truths are sacred: the Ọgbánje’s spirit stone (iyi-uwa) must be destroyed to break its cycle. But how we show that through practical effects, symbolism is where artistry thrives.

Filming in Montana posed visceral challenges. With few Black actors nearby, Kanaga scoured diaspora communities for performers fluent in Igbo idioms. “A mispronounced word shatters immersion,” he notes. When budgets ruled out CGI, the Ọgbánje spirit’s transformations emerged through shadow puppetry and silk-draped dancers, echoing traditional masquerades.

The location itself became a metaphor. A climactic battle in a Montana river, standing in for the Niger Delta, reflects what Kanaga calls “geography of displacement.” Just as immigrants straddle worlds, so do his spirits: “Ọgbánje isn’t lost in America, she’s recontextualised.”

The film’s haunting power is anchored by its ensemble cast, including veteran actress Stella Damasus, Florence Onuma, Moriyah Faith Jackson (Kamsi), Kenneth Okolie, and Oliver Haeden. Damasus delivers a shattering portrayal of a mother’s battle to save her daughter from an ancient spirit. Off-screen, her collaboration with Kanaga proved vital as co-producer, helping secure veteran talent while honouring the story’s Igbo roots.

Kanaga isn’t alone. At Sundance 2024, CJ Obasi’s Mami Wata, a monochrome fable of water deities defending a coastal village, won critical praise for weaving feminist resistance into folklore. Dika Ofoma’s Kachifo (premiering at Locarno 2025) reincarnates star-crossed lovers across lifetimes, while his short God’s Wife pits Catholic modernity against punitive widowhood rites.

“These aren’t nostalgia pieces,” Kanaga insists. “Obasi uses Mami Wata to dissect power. Ofoma makes reincarnation feel urgently romantic. We’re reclaiming our cosmology as a living language.”

Yet barriers persist. Kanaga notes Mami Wata’s muted Nigerian release despite Sundance acclaim:

Audiences here still favour familiar genres. We must build distribution bridges alongside creative ones. His critique cuts deeper: African Folklore isn’t ‘lazy’ storytelling, it’s our hardest, most necessary work. We’re sitting on a goldmine and calling it dust.

Kanaga’s frustration ignites when asked if Nigerian folklore is underrepresented: “It’s not underrepresented—it’s unexplored! We have hundreds of myths ripe for reinvention. Mami Wata proved it: use an urban legend to unpack the wounds of colonialism. Folklore is a lens for modernity, community, environment, identity.”

“These stories regenerate,” he says. “Like spirits, they demand new vessels.” For Kanaga, Water Girl’s impact is personal: “After years of doubt, ‘Will anyone care about spirits?’—seeing audiences react… I knew. This is my path. Rejections? Proof I’m carving niches only I understand.”

Kanaga shares a private “Water Girl” link as our call ends, a tangible thread to his spectral heroine. The gesture feels sacred. Like the iyi-uwa, the spirit stone that binds the “Ọgbánje”, it connects worlds: past and present, Nigeria and Montana, myth and medium. In Kanaga’s films, Obasi’s liquid luminescence, and Ofoma’s time-hopping romances, Nigerian cinema isn’t resurrecting ghosts. It’s inviting them to speak. And as Water Girl flows toward festivals, its message ripples clearly: the ancestors aren’t silent. They’re scripting the future.

The “Water Girl” will premiere soon, but you can watch the teaser here.

READ MORE: Why “The Fire and the Moth” Feels Like Taiwo Egunjobi’s Truest Story

About The Author

Related Articles

Burna Boy, Rema Lead Nigerian Sweep at Afrima 2026

Nigerian artists dominated the 9th All Africa Music Awards (Afrima), which wrapped...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 15, 2026Burna Boy, Davido, DJ Maphorisa Lead AFRIMA 2026 Race

Africa’s biggest music awards ceremony is shaping up for an intense contest...

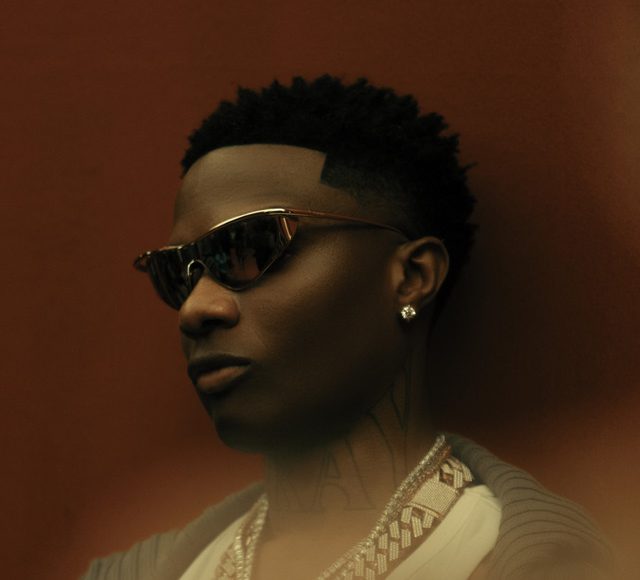

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 10, 2026Wizkid Makes History as Africa’s Most Streamed Artist on Spotify

Wizkid has become the first African artist to surpass 10 billion streams...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 10, 2026Burna Boy Caps Historic Year as Africa’s Most Streamed Artist on Spotify

Nigerian superstar Burna Boy has ended 2025 as the most streamed African...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 3, 2026

Leave a comment