“Nigeria’s accent dilemma: The Hannoying struggle with Inferiority”

A TikToker known as “BlackEnglishman,” with a bio that reads a “connoisseur of English pronunciation,” is a subject of ridicule and admiration online. His niche involves providing elocution lessons to Nigerian children, guiding them in the nuances of British English pronunciation. However, his efforts often transform into a spectacle due to his own lack of grasp of capturing the correct tone of British English becomes evident, which makes sense considering his non-British background. But, in an attempt to showcase the elocution of “British” English, he and his students inadvertently project what should only come out of a comedy show.

Nigeria’s diverse linguistic landscape comprises a wealth of over 500 languages. As a legacy of British colonialism, English has become the official state language, integral to education, government affairs, and daily social interactions, currently spoken by around 20% of the population. This linguistic framework coexists with three main indigenous languages— Yoruba, Hausa, and Igbo. In 2023, Hausa led as the most spoken local language, spoken by over 48 million individuals, followed by Yoruba, Nigerian Pidgin and Igbo. Nigerian Pidgin is a form of colloquial English and a common variety among Nigerians. Within this spectrum of linguistic diversity, there are different perceptions about the usage of indigenous languages and English. The tone and utilisation of English are significantly influenced by educational background and regional dialect, introducing variations that impact the auditory “quality” of one’s English.

Historically, proficiency in English has served as a symbol of social standing and educational attainment, positioning individuals more favourably in society as they are seen as educated and well-exposed. In more recent times, this paradigm has not shifted, but it has evolved. A noticeable trend in social dynamics is the growing inclination towards adopting Western-sounding accents. A pronounced local accent is viewed as undesirable, unattractive or “local” while speaking English. This cultural shift is evident in the criticism directed at individuals exhibiting what is commonly referred to as the “H” factor, specifically the presence of the H sound in certain words, a characteristic often associated with the Yoruba language. As societal attitudes evolve, the dynamics of language use continue to play a crucial role in shaping perceptions of social status.

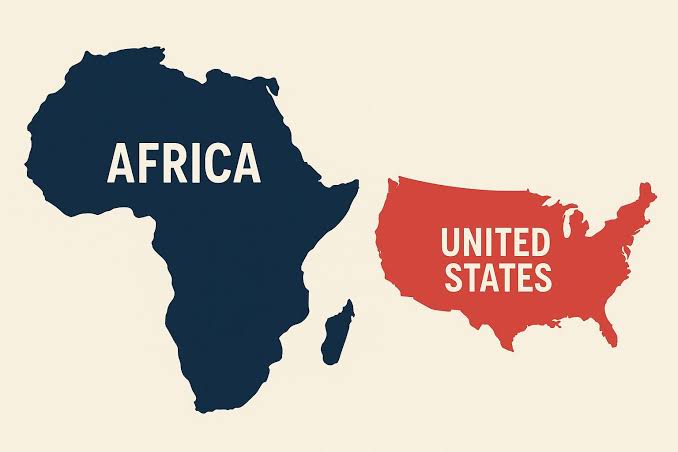

Globally, the standard British English, as taught in British schools, is widely preferred and regarded as the correct form. Nevertheless, many English-speaking countries diverge from this standard due to the sway of regional dialects and indigenous languages, which significantly shape their linguistic expressions and communication styles. This tendency is particularly pronounced in former British colonies, such as Nigeria, India and Singapore. Although there is no straightforward connection between having a regional Nigerian accent and one’s educational level or refinement, society often stigmatises individuals who do. This tendency reinforces the notion that westernisation and proximity to whiteness are superior, inadvertently fuelling Afrophobic narratives.

Popular culture

It’s not uncommon to observe on TV or radio that hosts tend to embrace what is perceived as more “international” accents (or colloquially known as “foneh”), whether authentic or not. This choice is often made because having a different accent positions them as more sophisticated, thereby elevating them above the average Nigerian. This accent bias ultimately serves as a significant form of social currency for many individuals, as the ability to project a certain accent is sometimes a determining factor that impacts access to certain privileges and opportunities within Nigerian society. This holds true, particularly in Nigeria’s broadcasting industry, where it is reported that aspiring broadcasters are frequently met with linguistic discrimination. In an interview, senior Broadcast Journalist and presenter on the BBC World Service, Peter Okwoche, stated that “proprietors want to have people with foreign accents on their stations. Good English doesn’t have an accent; it is just good English…There is so much inexperience on Nigerian airwaves these days, and that’s scary. Once you have a pretentious accent, stations want to snap you up”.

Ambiguous accents are not limited to the broadcasting industry; they can also be seen among Nigerian celebrities, such as Wizkid. Despite being born and raised in Nigeria and having never ventured beyond Nigerian borders before achieving fame, he has become notorious for adopting a questionable new accent. This phenomenon is further highlighted in a viral comedic video that circulates almost the diaspora annually on the 24th of June. Research has indicated that accents do tend to solidify and become permanent around the age of 12. However, it’s noteworthy that accents can undergo changes over time, and adults may acquire subtle accents, especially after residing in a foreign country for an extended period. The extent to which accents can evolve varies significantly among individuals and is influenced by many factors. A consensus among most scientists is that completely eradicating an accent is extremely challenging, leading to the widely accepted notion that accents, for the most part, endure permanently.

The controversial figure, Bobrisky, is another example, drawing attention and ridicule for the caricature-like adoption of a Westernised accent. In an unending effort to convey a sense of prestige and elevation, Bobrisky’s cartoonish endorsement of this accent becomes a subject of scrutiny and amusement in popular culture. When coupled with Bobrisky’s colourist beliefs, it becomes evident that an ongoing identity crisis influences how individuals present themselves, aiming to appear more refined, often manifested through the adoption of Western characteristics.

Education, colonialisation and Afrophobia

Writing In “Black Skin, White Masks, Franz Fonan states, “Every colonized people – in other words, every people in whose soul an inferiority complex has been created by the death and burial of its local cultural originality – finds itself face to face with the language of the civilizing nation; that is, with the culture of the mother country. The colonized is elevated above his jungle status in proportion to his adoption of the mother country’s cultural standards. He becomes whiter as he renounces his blackness, his jungle. Here lie the seeds of self-hate, the most destructive of the effects of colonialism.” This encapsulates one of the global challenges faced by black individuals and, in the Nigerian context, the unsettling connection between one’s level of sophistication and their proximity to whiteness and Westernisation. This complex has given rise to a pervasive inferiority mindset, contributing to various social and cultural issues that have fostered stereotypes within African communities. This point becomes even more apparent when comparing the reception towards non-British Europeans speaking English to that of Africans. The former is often perceived as more desirable and attractive, while the latter is generally not.

It’s not uncommon to hear that Nigerian parents may refrain from reinforcing the use of their native language within their homes. This is rooted in the desire for their children to primarily communicate in English. Despite the resistance to acknowledging it, this mindset is deeply rooted in a colonial mentality that places proximity to whiteness on a pedestal, deeming anything native as inferior. Unfortunately, this approach has led to a generation that has, to some extent, lost connection with its cultural heritage. This detachment can be attributed to the adoption of neo-colonialist and socially prejudiced Afrophobic attitudes, where being native is erroneously equated with a lack of exposure and sophistication.

The notion that proficiency in English is synonymous with advancement and that native languages are redundant has inadvertently contributed to the erosion of linguistic and cultural ties within Nigerian households. The implications of this trend extend beyond language, impacting the transmission of traditions and values. The aftermath is a generation, particularly in the diaspora, that is now grappling with the challenge of reconciling its identity within the context of societal expectations influenced by social biases. This highlights the need for a more nuanced and balanced approach to language and cultural preservation, creating an environment where linguistic diversity is celebrated and heritage is regarded as an asset rather than a hindrance to progress.

Interestingly, despite the unintended comedic nature of the elocution lessons, by the “BlackEnglishman” he continues to thrive in his business, still drawing support. This paradox arises because, even though his rendition of British English may sound like a mishmash of various accents under the sun, the Nigerians aspiring to assimilate into Western culture perceive it as desirable and superior, revealing the perception of certain accents as markers of cultural refinement. However, this should not be misconstrued as a justification to overlook the significance of speaking acquired languages fluently and prioritising the attainment of accurate pronunciation. The significance of accurate pronunciation in language use reflects a strong command of a language, enabling individuals to communicate more effectively with others.

Claiming that accent privilege is non-existent and individuals with more Westernised accents aren’t beneficiaries of such bias would be insincere. There is, however, value in acknowledging the potential power of a collective refusal to uphold Western ideals as inherently better. The ongoing association with Westernisation and elevation reinforces the perception of “Africanness” as inferior, an epidemic that has subtly infiltrated collective consciousness. Only through the rejection of this can the Afrophobic narratives start to weaken. By actively challenging and denouncing these concepts, we can forge a space where being authentically African is genuinely celebrated.

Read more: Media Trust takes too much Editorial Freedom – Information Minister

About The Author

Related Articles

Sovereignty for Sale? African Leaders Under Fire for “Lopsided” US Health Deals Linked to CIA Mind Control Research

A diplomatic firestorm is sweeping across Africa after 17 nations signed on...

ByWest Africa WeeklyFebruary 27, 2026Rivers: Tinubu’s Hidden Obsession

You cannot tell who a man is until he is in power...

ByJohnson AkorApril 14, 2025Mental Health Matters: Building a Foundation for Wellness and Growth

Writing has made me reflect on the power of sharing knowledge—sparking conversations...

ByOluwaseun DawoduDecember 13, 2024Paris 2024: Tobi Amusan And The Olympic Dream

The long-awaited Olympic year is finally here. The event, scheduled in Paris...

ByJunaid OlaitanJuly 24, 2024