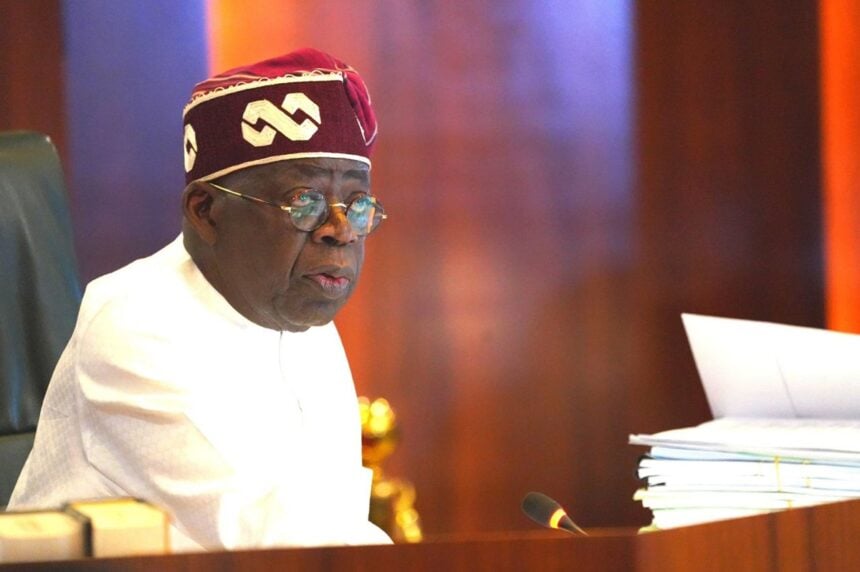

Nigeria’s decision to reject the use of private military contractors sits at the intersection of principle, politics and national insecurity. President Bola Tinubu has repeatedly insisted that Africa must lead its own security solutions, arguing that outsourcing counterterrorism to foreign mercenaries undermines sovereignty and weakens long-term institutional capacity. The government’s position aligns with that of the African Union, which discourages reliance on private military firms whose operations are often opaque, profit-driven, and challenging to regulate.

But this principled stance exists alongside a harsher reality: Nigeria’s security architecture is overstretched, under-resourced and struggling to contain the evolving threats posed by insurgents, bandits and extremist groups. From the Northwest to the Middle Belt, criminal networks operate with growing sophistication, exploiting gaps in intelligence, weak border control and limited state presence in many rural regions. The cycle is painfully familiar: attacks occur, victims are abducted, and security forces launch rescue efforts that often come days later. Prevention remains the system’s greatest weakness.

This is where the debate becomes complicated. While rejecting mercenaries is a legitimate strategic choice, many Nigerians question whether the state currently has the capacity to mount the kind of coordinated, rapid-response operations needed to stem rising violence. Countries like Mozambique and even Nigeria itself have previously turned to private contractors during periods of crisis, with mixed outcomes. Supporters of external assistance argue that private military outfits offer specialised skills, aerial firepower and rapid deployment capabilities that conventional forces may lack. Critics counter that their involvement can raise human rights concerns and lead to long-term dependency.

At the heart of the issue is not whether Nigeria “should” or “shouldn’t” hire mercenaries, but whether the existing security structure is capable of protecting citizens without them. Recent mass kidnappings, from worshippers in Kwara to schoolgirls in Kebbi and pupils in Niger State, have shown how vulnerable the country remains. The fact that abductors can move freely across state lines, hold victims for days and negotiate with little fear of arrest highlights deeper systemic flaws.

READ MORE: Zamfara’s Mass Wedding Raises Fresh Alarm About Welfare, Religion, and the Rights of the Girl Child

Tinubu’s emphasis on African-led solutions reflects a desire for long-term institutional stability. However, ordinary Nigerians are more focused on immediate safety, and for them, the philosophical argument holds little significance if insecurity continues to escalate. The government’s rejection of private military firms may align with regional norms. Yet, it also heightens expectations for a security system that has consistently struggled to prevent attacks or dismantle criminal networks.

Ultimately, the debate exposes a painful truth: Nigeria is at a crossroads where principles collide with urgent realities. Without significant investment in training, intelligence, technology and accountability, the country risks relying on rhetoric while citizens continue to suffer the consequences of an underperforming security system.

About The Author

Related Articles

Tinubu Deducts N100bn Monthly From Federation Account Without Approval El-Rufai Alleges Says Action Deserves Impeachment

Former Kaduna State Governor Nasir El-Rufai has launched a blistering attack on...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 26, 2026After Taiwo Oyedele’s Denials, Lagos State Activates ‘Power of Substitution’ Under Tinubu-Altered Tax Law, Allowing Authorities to Redirect Payments Without Court Orders

Lagos State has moved to activate a controversial enforcement provision in the...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 26, 2026Ivory Coast to Buy Unsold Cocoa to Support Farmers

Ivory Coast has announced a government plan to purchase unsold cocoa stock...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 23, 2026Ghana Moves to Reclaim Kwame Nkrumah’s Former Residence in Guinea

Ghana has embarked on a diplomatic and cultural initiative to reclaim the...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJanuary 23, 2026

Leave a comment