Opinion: Their Tribal Loyalties Are Stronger Than Their Sense of Common Nationhood

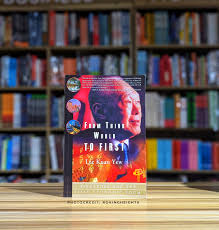

A REVIEW OF LEE KUAN YEW’S FROM THIRD WORLD TO FIRST

Regarding narratives about countries rising from dust to gold, the success story of Singapore ranks exceptionally high in the world today. A mere entrepôt, formerly occupied by the British imperial crown, was turned into a megacity-state by a group of nation-building marshals spearheaded by Lee Kuan Yew. Such a feat could only have been achieved by a responsible and responsive leadership, not by tongue-twisting empty mantras mouthed by copiously impervious imps.

Comparing Singapore to Nigeria reveals a pathetically agonising pain that stings to the bone marrow. Singapore gained independence in 1965 (five years after Nigeria gained its own). While Nigeria started with a GDP of $4.2 billion in 1960, 4.4 per cent of that, i.e. $975 million, was what Singapore started with in 1965. Singapore’s economy experienced a meteoric rise and stability during Yew’s tenure in government; Nigeria’s economy, on the other hand, tumbled as a result of incessant political instability and the IMF’s Structural Adjustment Programmes.

Leaders of Singapore have been able to raise the country’s GDP over the decades, which stands at $514.47 billion this year, whereas Nigeria’s GDP has crashed from a 2014 benchmark of $574.2 billion to $187.64 billion today. Although their contexts varied, Nigeria’s economy has struggled with a thin record of growth, while Singapore’s has thrived despite a few instances of economic shocks. Nigeria’s economy is failing in a dangerous and exponential manner.

Several factors have contributed to Singapore’s outstanding success story, including exceptional leadership, excellent statecraft, principled teamwork, institutional discipline, the rule of law, prioritising public security over private security, rational organisation of labour, and the fostering of work values and a nationalist spirit in education, among others. The autobiography is fully packed with narratives of Yew’s admirable team-building skills and his journey since becoming Prime Minister in 1965, until he retired from public service in 2004.

In ‘Inside the Commonwealth Club’ in particular, one of the book’s chapters, Yew highlighted his encounters with leaders of countries from around the world. Commonwealth Club—more or less an association of prime ministers of ‘former’ British colonies— hosted meetings rotationally. It was during the Nigerian edition of the Club meeting in 1966 that Yew made some observations on the first set of administrators of post-independence Nigeria and Africa. His observation on Nigeria is worth mentioning.

Yew’s comments on Nigeria in the book offered insights into the nature of the country’s First Republic politicians, primarily revealing how they differ slightly from Nigerian politicians of today. Yew met Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa and then Finance Minister, Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh, during the Commonwealth Club meeting, which was held in Lagos on 11-12 January 1966—just three days before Nigeria’s first military coup terminated the lives of those two eminent personalities and several others.

Pertinent to note that Yew’s account of his visit to Nigeria is a peculiar time-marker in the annals of Nigerian history. His encounters with Nigerian leaders and leaders of other African countries at the time, in most Club meetings, allowed him to form hypotheses about African leadership. His hypothesis about the emotiveness of many African leaders is an observation of his that calls for thorough introspection. As Africans, we may not need to discard emotion completely. Still, we must weave it with rigorous rationalism and revolutionary strides as the world evolves into a multipolar world of unapologetic realpolitik.

Yew stretched his observation on African leaders much further by accusing many of them of being loyal to their ethnic enclaves rather than to “their sense of common nationhood”. How could he say such a thing? In fact, how dare he? The question should be, did he tell the truth or a lie?

Yew’s comments might come off to some Nigerians as something to relish. Perhaps if he had said it at the dawn of Nigeria’s 1960 ‘independence’—we all might have given a toast to it. Instead, in this twenty-first century, we should take it as a condemnation of our parochial politics and also a summons to us Nigerians to collectively mourn Nigeria’s wasted decades of opportunities to forge a nationalist identity from our diversity and adversity.

When we are done mourning, perhaps we should also be sober enough to take action to abolish every form of ethnic union, regulate religious organisations, and begin to form cross-ethnic, cross-religious loyalties to kickstart a shared sense of nationhood process. Can we?

Singapore was not without its diversity—Yew explained this in the book. Singapore is broadly categorised into Chinese, Malay, Indian and ‘Others’, with Chinese making up the largest group. Religion was diverse in Singapore as well. There are Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Christianity.

These layers of diversity should have been a recipe for disaster—it was not! However, it nearly happened in small situational cases where Chinese-Malay race riots sparked. It almost spread to adjacent locales, had it not been for the timely intervention of Yew and his cabinet ministers, and the fairness they implemented with acute transparency. Besides, thanks to truth-telling reportage, the Yew-led government demanded that all local and foreign media outlets, or else they would have blown the narratives of those race riots out of proportion for their agenda or a foreign-sponsored agenda.

Singapore was fortunate to have Yew at the helm of its affairs at a very critical juncture of its post-colonial takeoff. Throughout the pages of the book, one could hear the subconsciousness of a pious nationalist and statesman. Like Singapore, Nigeria was fortunate to have nation-building leaders like Nnamdi Azikiwe, Kingsley Ozuomba Mbadiwe, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, Margaret Ekpo, Eyo Ita, Obafemi Awolowo, Aminu Kano, Ahmadu Bello, and several other eminent figures at the dawn of the country’s independence.

What happened? It was ethnic and religious politics which some of Nigeria’s state actors manipulated at every whim and chance in collusion with Western secret agents. Suppose we are to replicate Singapore’s success in Nigeria. In that case, we must seek out genuine nationalists/pan-Africanists amongst us, build a power base around their ideas, and actively eliminate bigotry from public and private discourse. And we must, by ourselves, begin to Nigerianize all ethnic unions in the nooks and crannies of Nigeria.

Additionally, we must take grassroots education of the masses seriously through the use of theatre in building a Nigerian Nationalist Front. Our people must understand the internal and external factors behind their worsening sufferings.

Yew was hardly a figure that had time for frivolities, and it showed in the experiences he shared in the book. All his global trotting from one region of the world to another was, in truth, for the benefit of the people of Singapore, Southeast Asia, and Asia-at-large. Yew’s book would convince anyone who cared to look beyond the words that the crux of his memoir is that statecraft is a serious and delicate affair.

Yew died 10 years ago at age 91. Yet, to this day, his name resurrects on the lips of those who craved for their own countries what he and his team of principled doers achieved with Singapore. Olusegun Obasanjo was reported to have spoken highly of Yew during his tenure as a civilian president of Nigeria (1999-2007). We may be forced to ask, what example did he set, despite revering Yew as a role model? Yew’s name and Singapore’s will ring bells for a long time.

As Nigerians, we should not be religious about our problems or blame an entire ethnic group for our woes; if Yew and his team had behaved as such, Singapore would have stayed ‘Third World’. The problems obstructing our sense of common nationhood are real, and we must, through our sweat and blood, find genuine and revolutionary solutions to them.

Read More:

- As Nigeria’s FCT Minister Wike Grab Lands, Schools Remain Closed and Teachers Unpaid

- The Polytechnic Ibadan Students Protest Renaming Of Institution In Honour Of Late Governor Olunloyo

About The Author

Gbọ́láhàn Adébíyì

author

I am a writer and historian who works as a part-time researcher at the National Archives Ibadan. I have research experience in ‘Nigeria-Biafra War’, ‘Lagos Colony’, ‘Maternal Mortality’, and ‘British Colonial Army in Nigeria’. My research interests involve War & Diplomacy, literature review, African foreign affairs, religion & politics, religion and non-religion, tradition and modernity. I have self-published works at adebiyigea on Substack. Some of my essays are published on The Republic.

Gbọ́láhàn Adébíyì

I am a writer and historian who works as a part-time researcher at the National Archives Ibadan. I have research experience in ‘Nigeria-Biafra War’, ‘Lagos Colony’, ‘Maternal Mortality’, and ‘British Colonial Army in Nigeria’. My research interests involve War & Diplomacy, literature review, African foreign affairs, religion & politics, religion and non-religion, tradition and modernity. I have self-published works at adebiyigea on Substack. Some of my essays are published on The Republic.

Related Articles

The APC Effect: 10 Years That Crippled Nigeria’s Economic Future

A decade after the All Progressives Congress (APC) came to power on...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJuly 3, 2025‘Tinubu’ Now Christened on Airports, Barracks, and Possibly Mass Graves

In a country where hunger kills faster than bullets and terrorism has...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJune 26, 2025In Africa, Steal a Phone and Die — Steal Billions, Gain Power

In many parts of Africa today, justice wears two faces. One is...

ByWest Africa WeeklyJune 26, 2025Faith, Tribe, and the Failure of Unity in Nigeria

In Nigeria, the issue of who you’re begins with where you’re from...

ByIkenna ChurchillJune 23, 2025

Leave a comment